The Churchyard of St. Luke’s, Hickling

(by Carol Beadle 2024)

- Introduction

- Nature And Wildlife

- The Black Poplar Tree

- The Cherry Tree & Fred Maltby Warner

- There But Not There

- The Coronation Bench

- Bench Mark

- Sun Dial

- Tree Of Life

- The Weather Vane

- The Church Clock

- The Church Porch & Door

- Hickling Churchyard And The Civil War

Burials In The Churchyard

- Introduction

- The Burial Pit

- Buried In Wool

- Belvoir Angel Gravestones

- Victorian Burials

- Modern Burials

- Ashes Section

INTRODUCTION

Hickling Churchyard provides the pleasant surroundings and the backdrop to the visual impact of St Luke’s Church. It is hidden from the road and most people only take a cursory glance if they are walking past. After reading this booklet, it is hoped that the importance of the churchyard both as a piece of the social history of Hickling and as an asset to the community will be seen.

The Churchyard is the land which surrounds the Church which has been consecrated by a Bishop and where people have been buried. It is sometimes known as ‘God’s Acre’.

Churchyards can be hosts to ancient and unique habitats because they have possibly remained unchanged for hundreds of years. The land has not been ploughed or cultivated. Step through Hickling Church gates and enjoy the birdsong; admire the wild flowers; and watch the birds and insects. The virtual isolation from modernity makes this graveyard a wildlife friendly environment.

Hickling Churchyard may be older than Christianity and is certainly older than the church. It was perhaps originally used for some kind of pagan ceremony. As people remained slightly heathen long after they had theoretically been converted to Christianity, many churches like Hickling were built on a former pagan site.

The first burials in Hickling Churchyard probably took place before the church was built and the religious ceremonies which took place there are sure to have been pagan. Consider this if only 4 burials a year have taken place in Hickling Churchyard for the last 1000 years, there are over 4000 bodies buried in this small churchyard.

When the Romans came, they preferred cemeteries away from the place of worship but this practice was not generally accepted by the locals.

In Saxon times the churchyard was used as a place for taking oaths and dealing with disputes. Hickling Churchyard would have been the centre of the community. People would have passed through the churchyard to conduct business in the church porch which was the place where agreements of a binding nature were transacted. Merchants may have set up stalls at the side of the church.

In Medieval times Hickling Churchyard would have been the centre of village life and much of what went on there would be unthinkable today. Children played in the churchyard and the best known, surviving game they played is the game of ‘fives’. Archers practised their skills and would have used the church stone walls to sharpen their arrow heads. Market stalls would be here also. Eventually, local penalties were imposed for those playing sports in the churchyard.

For the rich, burial within the church itself was preferred. For those who could not be buried inside the church, the churchyard became the next best thing. The most favoured sites were those to the east, as close as possible to the church. In such a location, the dead would be assured the best view of the rising sun on the day of judgement. People of lesser distinction were buried on the southside, while the north corner of the churchyard was considered the ‘Devil’s Domain’. It was reserved for stillborn, bastards and strangers who were unfortunate enough to die while passing through the local parish.

Suicides, if they were buried in consecrated ground at all were usually deposited in the north end of the churchyard. Their corpses were not allowed to p-ass through the church gates and such bodies were passed over the hedge as far away from the church as possible.

Most churches have a main entrance to the churchyard and a small entrance from the rectory which would have been used by the vicar. Hickling churchyard entrance is not very impressive and the wrought iron gates were possibly installed during the Victorian era. What the gates do is to separate the ordinary land from the consecrated ground of the churchyard. Some churches have a lych gated entrance. The term ‘lych’ is a Saxon word for corpse. The lych gate was traditionally a place where corpse bearers carried the body of a deceased person. The priest would carry out the first part of the burial ceremony here under the shelter of the lych roof. There is no evidence to suggest that Hickling Churchyard ever had such a lych.

The lives of the people of Hickling and the economic and social changes in Hickling over the last 500 years can all be discovered in this churchyard. The Hickling History Group is endeavouring to do just that and welcome any help or information relating to Hickling Churchyard and the people whose names appear on the gravestones.

The rector holds the freehold of the churchyard. The Parochial Church Council has to maintain it but it is the duty of the Church Wardens to see that it is only used for its proper purposes. Although, it is now closed for burials, Hickling churchyard still remains the responsibility of the Parochial Church Council. In 2022, it cost £1800 for the upkeep of the churchyard.

NATURE AND WILDLIFE

Springtime is a good time to walk through the iron gates into Hickling Churchyard to discover the nature and wildlife in this secluded place. A magnificent place to take an easel and paints, a drawing pad or even a camera to capture this place at its most colourful.

An ancient churchyard would have been carved out of woodland or flower rich meadows, and Hickling is no exception. Over the centuries to the present day, the land around the churchyard has been ‘improved by the plough and artificial fertilisers or engulfed in housing and road development. However, inside Hickling churchyard, the grassland has remained comparatively untouched and locked in an ecological time capsule. In the churchyard there has been no crop spraying, no systematic and seasonal churning up of the land. Any seeds dropped by passing birds or carried by the wind will have a good chance of establishing themselves in the churchyard.

Perhaps the most beautiful and most primitive form of life in the churchyard is likely to be a type of lichen adhering to stonework or trees, In Hickling it appears in various shades from greyish green to red. Lichens are slow growing types of fungus and alga, which reproduce when spores drop from one growth provided that the cells of both again come into contact with each other. The resulting crust grows by feeding entirely on the atmosphere. This is why it may eventually cover whole areas of rock or stonework. It does not need water to survive and is very long living.

Some flowers which can be spotted in Hickling churchyard include cowslips, primroses, daffodils, orchids, bluebells, snowdrops, buttercups, violets, and daisies. As Hickling churchyard is now closed for new burials, the ground remains undisturbed. During the last 30 years, the importance of churchyards as a refuge for wildflowers has been widely recognised. Now many churches have sections of their churchyard left uncut. A charity called ‘Caring for God’s acre’ was set up in 2000 to encourage the preservation and conservation of churchyard flowers and foliage.

The abundance of such species as primroses and snowdrops in churchyards, with Hickling being no exception, can be partly attributed to the Victorians. Mothers grieving for their deceased young infants would plant these flowers as a memorial on their children’s graves.

Three flowers found in Hickling churchyard have symbolic religious connections; –

Lily of the Valley-this flower found in the churchyard with its tiny white flowers is a symbol of purity and humility and is often associated with Mary, the mother of Jesus.

Violet– this little flower can be found growing under the hedgerow and near ‘the Tree of Life’ in Hickling churchyard. It is sometimes thought to represent humility of Jesus who came down to earth as a man.

Clover– these 3 leaved plants are in abundance in Hickling churchyard. It is said that St. Patrick used a clover leaf as a visual aid when teaching about the Holy Trinity. Each leaf has 3 parts which are not 3 separate leaves but one leaf. Likewise, God is ‘God the father’, ‘God the son’ and ‘God the Holy Ghost’, and yet he is not three Gods but one.

Wildlife is also seen in Hickling Churchyard. Several species of birds and bats as well as hares, rabbits, foxes, squirrels, pheasants, field mice, and even hedgehogs have been spotted. In 2022, a pair of mallard ducks were found nesting here away from the now busy wharf area. Frogs and toads from the nearby streams have been seen also. On a hot afternoon a grass snake may be spotted slithering through the grass on the edge of the churchyard.

Many species of birds can be found in Hickling churchyard. House martins, swifts and house sparrows all swirl and dip around the tower during the day and the bats which do so at night, make their homes on or in the church building. Bats, probably the pipistrelle have been seen hanging from the roof beams. An owl may flap away as you enter the churchyard at dusk. In March, the noise from the crows is deafening as they build their nests in the trees. The trees themselves provide food for many species of insects which in turn feed a variety of birds.

A feature of British churchyards is the evergreen native Yew Tree – Taxus Baccata. The yew is a very slow growing and long living tree and it has been looked upon as a symbol of immortality and therefore a suitable tree to plant where people are buried. They can attain a height of 20ft-40ft. In fact, many yew trees found in churchyards are two or more trees that have welded themselves together so that the bark has completely obliterated their fusion. The yew tree has a characteristic fluted trunk and gnarled branches and its dense foliage is a familiar site in older village churchyards like Hickling. Some trees are over 800 years old.

The pre-Christian use of the churchyard site may have included pagan ceremonies in which yew foliage played a part. It is from this time that the yew became a symbol of everlasting life.

A lot of yews were planted by the clergy after the Conquest in 1066. Edward 1 decreed that they should be planted to protect the church from the elements as their thick, close growth protected the church buildings from gales and storms.

As the yew is poisonous to animals, farmers kept their livestock away from it and so the yew protected the churchyard. The yew berries though are eaten by birds thus encouraging them to nest nearby.

In medieval times, the Hickling villagers would have carried the foliage in Easter processions and spread it over graves. The yew was used to represent palms and for this reason Palm Sunday was sometimes known as Yew Sunday. Yew foliage would never have been found inside the homes of Hickling residents as it was considered to be a catalyst to death.

During the 13th and 14th centuries, the longbow was used very successfully in warfare. It was made using the wood of the yew tree.

In Hickling churchyard some headstones are found within the dense foliage of the yew growing around the headstone and engulfing it. A far different picture from when the headstone was first erected.

THE BLACK POPLAR

At the far end of the Churchyard, directly in front of the path stands a tree, which is about 30 metres tall. Few people give this tree a second glance and would parhaps not know how important this tree is. It has stood looking towards the Church for over 200 years. In the early 1900’s two trees stood in the churchyard but one has since died.

This tree is the NATIVE BLACK POPLAR TREE [populous nigra aap. Beulifolia], a tree which is now Britain’s most endangered timber tree. It is rarer than the Giant Panda!

The leaves are not as soft as other poplars and are clearly defined by their strong heart shape. They are large round trees with a straight trunk and a smoky grey bark. In their lifetime they grow about 35 metres tall with a 20-metre branch span and live for about 250 years.

Black poplars were once a familiar part of the British landscape. They were a component of floodplain woodland. This tree was found in valleys, besides farm ponds and near to rivers. About 30 years ago when a conservation officer from Southwell Diocese came to inspect Hickling Church, he noted the importance of the Black Poplar tree in the churchyard and commented that it was taking much of the water out of the ground and if this had not been happening the foundations of the church would have subsided causing great damage to the outer walls of the church.

The landscape artist, John Constable captured this magnificent tree in his 1821 famous painting, ‘The Hay Wain’.

The Black Poplar tree, along with oak provided much of the timber used in Britain up until the end of the 17th century. The timber is quite fire resistant and so was used for floor boards and roofing. The wood is shock absorbent and so this timber was the choice for rifle butts, wagon bottoms and horse stabling partitions. The main trunk is straight so was used for thatching spars and sheep pens. The forked trunks formed the structural support of cruck framed buildings. The wood is lightweight and light in colour so was used for clogs, furniture and fruit boxes. The ship builders took a large number of trees and their wood was used to build the ships used for fighting the Spanish Armada.

In 1973 it was thought that there were less than 6000 mature native Black Poplar trees left in the whole of the British Isles. In 1990, the County of Cheshire recorded that they had identified just 370 mature trees.

This tree has not reproduced naturally for many centuries and has been in decline over the last 300 years.

Pollination requires the presence of both male and female trees. It was estimated in 2000 that there were only 400 mature female trees left. The one standing in Hickling Churchyard is male and does not produce suckers.

Native Black Poplars can hybridise with other types of poplars so most seed produced trees seen around are not the true Black Poplar. Such hybrids can be seen along the Grantham Canal.

In the 18th century, faster growing American and European poplars were introduced and the popularity of the native Black Poplar declined. As a result, the trees which remain today are old and reaching the end of their lives. The one in Hickling Churchyard is over 200 years old.

The Church Wardens recently had the tree pruned at a cost of over £500 when to remove this tree and take away the wood would have cost much less at £350. It is thanks to those who know the rarity of this tree and had the foresight to keep it, that it still stands in Hickling Churchyard today.

The Kew botanist, Edger Milne Redhead did a survey of the number and distribution of Native Black Poplars from 1973-1985. He concluded they were endangered and he started a programme of propagating them from cuttings.

Roger Jefcoate, known as the Phantom Tree Planter is committed in his campaign in saving this tree from extinction. He spends his time combing Britain looking for places to plant Native Black Poplar saplings. He planted one in the middle of a roundabout in Milton Keynes.

In 2009, the Crown Estate under the guidance of the then Prince Charles [now King Charles 111] became involved in trying to save this tree from extinction. In 2010, they replaced 200 slips from the Dunster estate in Somerset [which is one of the few bastions of this native tree] ‘Unless something is done to try and increase the numbers we will end up losing the Native Black Poplar’…Prince Charles [King Charles 111]

In Suffolk 90 mature trees were identified and a project has been launches to take cuttings and when established to replant in suitable landscapes in the County where they can grow and mature.

In 2017, the Hickling Women’s Institute celebrated 70 years and members wanted to put something into the village to mark this anniversary, but not the usual bench. On hearing about the Native Black Poplar Tree in Hickling Churchyard reaching the end of its natural life, it was decided to purchase and plant such a sapling. With the help of the Parish Councillor and Hickling Parish Council, a corner of the cemetery was allocated for this tree. A tree was planted and when it grows it will be visible from the Church.

So next time you are in Hickling, walk along the Church path and at the end pause and admire this rare tree which has protected the foundations of Hickling Church for so long.

THE CHERRY TREE AND THE STORY OF FRED MALTBY WARNER

William and Frances Maltby lived in Hickling in the mid 1800’s with William making his living as a grazier/cottager. The couple had 4 children who were all born in Hickling – John Henry Maltby was baptised in Hickling Parish Church on 8 May 1855; Emily Maltby was baptised on 4 July 1859; Clara Maltby was baptised on 13 February 1864 and their youngest child was born in Hickling on 20 July 1865.

Later in 1865, the Maltby family made the decision to pack up and leave Hickling and emigrate to America. How long they had been planning to do this is unknown. At this time, America was just at the end of Civil War; Abraham Lincoln was the President and assassinated a few months after the start of his 2nd term of office and the west of America was ‘wild’

William and Frances Maltby left their relatives and friends in Hickling and with their 4 young children made their way to the port where their ship was waiting. It is doubtful if William and Frances had ever ventured far from Hickling prior to embarking on this venture.

Many questions have been raised concerning this emigration to America from England and the answers are not known but can be speculated upon.

- Why would they have wanted to leave Hickling with 4 young children?

- How was it arranged?

- How did the couple know about the opportunities awaiting them in America?

- Had other friends or neighbours gone also?

- How was the journey financed?

- What luggage could they take?

- How did they make their journey to the port, most likely Liverpool?

- What was life like aboard the ship?

- How long was the journey?

- When they arrived who was there to welcome them and help them start their new life in America?

William and Frances left Hickling full of hope, excitement and ambition to make a good life for themselves in America. Sadly, this did not turn out as planned.

Shortly after their arrival, Frances Maltby died, leaving William, a widower in a strange country with 4 young children to raise. He had no family to step in and help him and he found he was unable to cope.

William made what must have been a very difficult decision, to have his 3 youngest children adopted. Adoption did not exist as a formal framework in America at this time and so any adoption would have been made by an arrangement between the two parties.

The young infant, Fred was taken by P Dean Warner and in wife, Rhoda who were both in their 40’s and had no children of their own. They had previously adopted a daughter but wanted a son also. The Warners had a shop in Farmington in Oakland County, Michigan and it was in Farmington where Fred spent his early life.

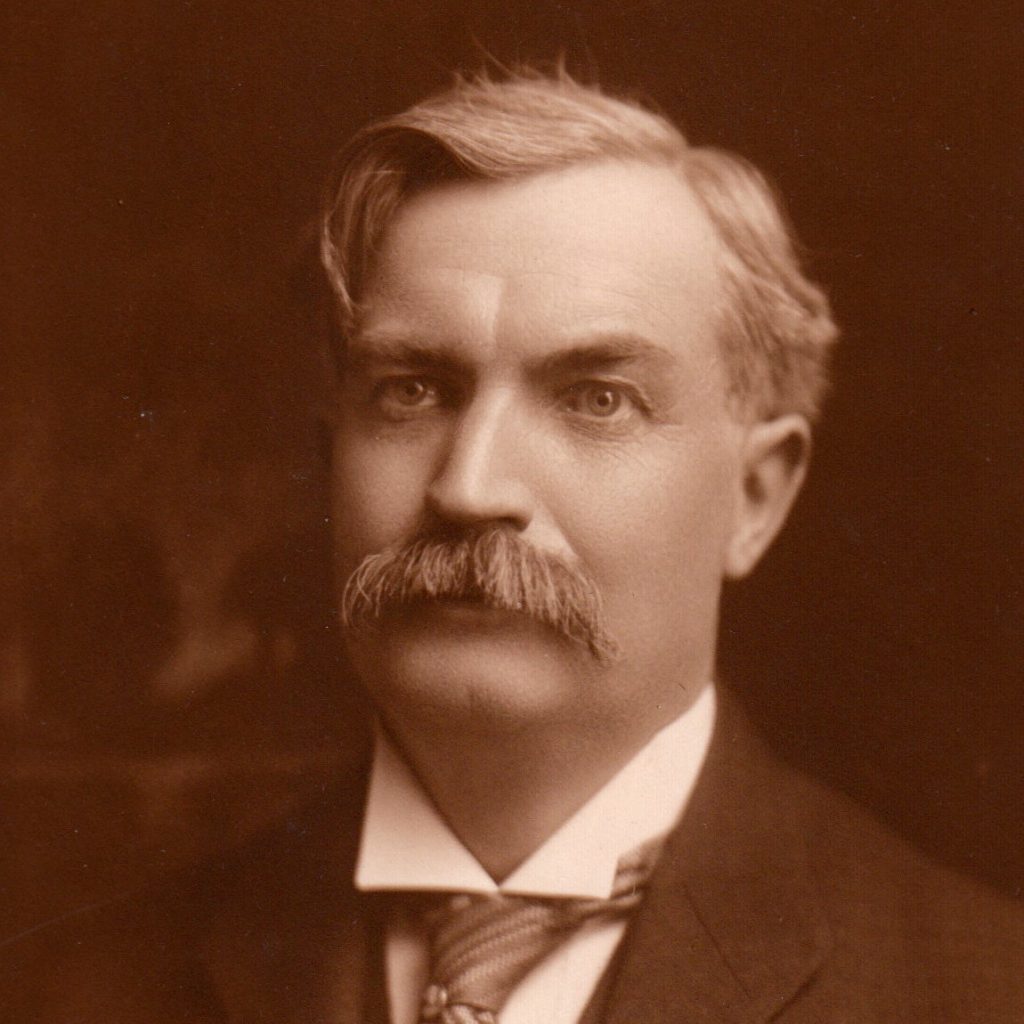

Fred Maltby became known as Fred Warner and despite his unfortunate start to life in America, the change of fate and circumstances meant he was given any opportunity he may not have had otherwise.

When Fred finished his schooling, he went to the Michigan Agricultural College for 1 year and then he went to work in his adopted father’s store. He later ran this store for 20 years.

In 1888, Fred married Martha M Davis of Farmington and they had 4 children who were all brought up as Methodists.

In 1889, Fred started a cheese business – was this his Hickling genes emerging as Hickling was very much a Dairy Farming Village with cheese making a cottage industry here. Cheese making has continued in this area with local milk now going to the nearby Long Clawson Dairy which was founded in the early 1900’s. Fred expanded until he had 13 cheese factories and became known as ‘The King of Cheeses’. He also became involved in farming and banking.

On top of his business enterprises Fred was deeply involved in Politics and a member of the Republican Political Party. He served on the Farmington Municipal Council and as a prominent citizen, he rose quickly in politics. From 1895 until 1898, he served in the Michigan Senate like his adopted father had. From 1901 to 1904 her served as the Michigan Secretary of State.

In 1904, he was elected Governor of Michigan and served 3 terms. He was the 26th Governor of Michigan, the first to serve 3 consecutive terms and THE FIRST FOREIGN BORN GOVERNOR. It was not an easy period to be Governor. At one point the State ran out of money to pay its employees and at another point the State Treasurer deposited a large amount of state funds in a bank which went bankrupt.

He was known as a progressive Governor advocating such policies as the regulation of the railroads, conservation policies, child labour laws and supporting equal rights for women. During his 6 years in office a Factory Inspection Bill was passed and there was a promotion of highway construction

After his governorship. Fred returned to his farming and business interests but was still involved in many organisations

His home was a large mansion in Farmington which is now a museum to his memory and run by a Trust. It is listed in the National Register of Historic Places in America and is open to the public. Inside the mansion is a room which tells the story of Fred’s humble beginnings in Hickling Village and includes lots of memorabilia sent by the Hickling History Group for display.

Fred Maltby Warner died on 18 April 1923 in Orlando, Florida of kidney failure. He was only 57 years old. He was buried in Oak Hill Cemetery in Farmington, Michigan.

In 1985 Susan Klingbiel, who was Fred’s granddaughter visited Hickling to see where her grandfather and his parents had lived. She met distant relatives who still reside in the village and neighbouring area.

On 21 September 1985, 120 years after Fred’s birth in Hickling, there was a short service in Hickling Parish Church in memory of Fred and his granddaughter presented the Church with a prayer book. After the service, a flowering Cherry Tree was planted in the churchyard opposite the Church Porch and close to the hedge. Each springtime this tree is full of pink blossom.

In 2020, our ‘friends’ who volunteer in the Warner Mansion in Farmingron sent Hickling Community two wine glasses engraved with Fred’s mansion. These were given to the Plough Inn to put on display so the public could see them. Next time you visit the Plough please take a moment to look at these glasses and reflect how the son of a poor cottager from Hickling became the Governor of Michigan, the ‘King of Cheeses’ and owner of this large and impressive mansion

‘THERE BUT NOT THERE’: COMMEMORATING 100 YEARS SINCE THE END OF WW1

In 2018 Hickling Village bought a ‘There But Not There’ life sized ‘Tommy’ silhouette which was funded by subscription from the community. They also bought 11 head and shoulder silhouettes to be placed on the pews in the Church to represent those men from Hickling who had lost their lives in WW1 and WW11.

These silhouettes first went on display on 4 May 2018 and are now put out regularly during Remembrance Services and other Commemorative events.

The life-sized Tommy is in Hickling Churchyard permanently. Have you seen him? He is moved around with the seasons and for special events to make the most impact. He stands with bayonet fixed [the formal position conventionally taken by a soldier when commemorating his fallen fellows] and his head is bowed in remembrance.

These silhouettes can be seen all over the country and the money raised from the purchase of the ‘Tommies’ went directly to the work carried out by charities aiming to Commemorate, Educate and Heal. The ‘Tommies’ were made by Royal British Legion Industries.

The figures remind us that humanity struggles to live in peace and it reminds us of the terrible cost when we fail to find that peace. This is relevant today as much as it was in 1918.

THE CORONATION BENCH

In 2023, following the death of his mother, Queen Elizabeth 11, her eldest child, Prince Charles was crowned, King Charles 111. The Hickling Women’s Institute to commemorate this event purchased a bench and had it suitably inscribed. This was paid from their funds at a cost of £450. The Church Wardens had often commented that there was nowhere to sit and relax in Hickling Churchyard and so permission was granted to place the bench here. Unfortunately, John Bloor, the Church Warden died before he saw the bench in but his son kindly laid a firm base and positioned the bench. To preserve it the Hickling WI have been cleaning and oiling the bench twice a year.

THE SUN DIAL

A form of sun dial has been used since Anglo Saxon times to indicate the times of Church Services. Anglo Saxon dials gave only a rough approximation of the time between sunrise and sunset. The early sun dials were scratched on the outer Church wall which was south facing. They are commonly known as ‘Scratch Dials’

The concept of a sun dial originated in the ancient world with its principle being easily and universally grasped. The sun appeared in the sky daily in a regular fashion, although people did not know how and why. The shadow cast by a stationary object moved around at the same speed each day as the position of the sun changed. Hence, the shadow from a metal rod, fixed into the Church wall would fall along the same place each day at the same time.

The particular interest was in noon and the times of important Church services such as mass and evensong. These were sometimes indicated by strong lines which radiated from the central pin.

Old dials can be found almost anywhere on the south facing walls of churches and many, like the one on Hickling Church are not now obvious. Most sun dials have now lost their indicator rods and have themselves become eroded. The large outward splayed hole where the rod once was means that as it rusted away it wore away the stonework until it dropped out. What remains is a faint rough circle with a central hole and lines radiating out from this about 15 degrees apart. This is all that there is left of the one on the wall of Hickling Churchyard and hardly anyone would realise a sun dial had once been here.

A problem with sundials is that they could only be relied upon during daylight and when it was sunny It was difficult to be able to ring the bells with any accuracy calling people to church.

It was not until the 15th century that the day was divided into 24 and mechanical clocks easily seen from afar soon replaced the sun dial .

THE BENCHMARK

There is a benchmark etched into the outer wall of the Church near the base of the tower and to the left of the ‘Tree of Life’ stone.

The term ‘benchmark’ is sometimes also known as a survey mark. Such benchmarks are not unique and originally about 500,000 were created across Great Britain. However, with demolition and remodelling of buildings and infrastructure changes, benchmarks are becoming increasingly rare. Originally the majority of these marks were located in urban areas, but those surviving are found now mostly in rural areas where there has been less modernisation.

Today many people do not know what benchmarks are and so perhaps that is a reason they are not maintained and protected. Local planners do not seem to insist they are preserved when properties are extended and externally changed. One benchmark on a house on Hickling Pastures disappeared entirely when the house was extended a few years ago. At the moment [2024] there is another bench mark on Hickling Pastures found on Sycamore Lodge, the former home of the Chahal family.

Benchmarks started to appear in Great Britain in 1840 when ordinance survey mapping commenced. Benchmarks were used as a means of making ordinance maps accurate.

Benchmarks traditionally are a chiselled out arrow and a horizontal mark which the surveyors made in stone structures. The idea was that an angle iron could be placed in the horizontal mark to form a ‘bench’ for a levelling rod. This fixed horizontal line ensured that a levelling rod could be accurately repositioned in the same place in the future.

These benchmarks were fixed points which were used to calculate the height above the mean sea level. A whole systematic network of levelling lines spread across Great Britain. Moist villages had about 6-8 benchmarks but towns had many more. They were etched into permanent features such as churches, houses, bridges and even stone horse troughs.

If the exact height on one benchmark [BM] was known the exact height of the next could be found by measuring the difference in height through a process of spirit levelling. Subsidence, often due to mining, has affected the accuracy of the levelling values today.

Today, surveyors use GNSS [Global Navigation Satellite System] technology and what would have taken days or maybe weeks in the past , now takes just a few seconds.

Benchmarks remain as a nostalgic reminder of how Britain used to be mapped.

THE ‘TREE OF LIFE’ STONE

As you walk up the pathway towards Hickling Church, you are almost facing the most fascinating and unique item in Hickling Churchyard, yet few people notice it. It is a decorated piece of stone set into the lower part of the outside west wall stone work of the Church

This stone is believed to date from the 13th century but little is known about it. It may have originally been a coffin lid and at some point, it was found lying in the churchyard and an enterprising stonemason incorporated it into the church wall.

When the Danish invaders came to the North of Britain, they brought with them new ideas for decoration and design. Their art sometimes being inspired by that of the Mediterranean region. One design often seen was the ‘Tree of Life’ and it is this design which is found on Hickling’s stone placed in the Church wall. This design is often seen in the North of England but to find it so far south is quite unusual.

The Tree of Life is a universal symbol found in many religious traditions around the world. It symbolises life itself with its branches reaching for the heavens and its buried roots linking to mother earth. Many ancient mythical stories come from the idea that all living beings are born from the earth, the source of life and subsistence for all. In pre-Christian paganism, the Vikings believed that the world was built upon a great tree known as ‘Yggdrasil’

The tree became a symbol of love, wisdom, rebirth, strength, redemption, friendship, beauty and encouragement.

The Hickling Tree of Life stone is set horizontally but clearly the design is intended to be seen vertically. On the right-hand side are the tree roots with engraved steps coming up from beneath the earth to ground level, The tree design itself is very fluid with 3 sets of branches reaching out from the ‘central tree trunk’. At the top is a circle of branches with a central cross.

During the last 20 years the stone has begun to show deterioration perhaps due to acid rain and with no protection against wind blowing rain directly onto the stone. It is regularly inspected by Church Officials and there has been much discussion as to how it can be protected against further decay but to date nothing has been decided upon.

In recent times there has also been much interest in the stone and perhaps more information will come to light about it.

THE WEATHER VANE

Erected high on the top of Hickling Church is a weather vane. The word vane is an old English word meaning ‘flag’.

A weather vane is a device for showing the direction of the wind. Their first appearance was as early as 139BC in China. They are usually a thin plate of metal which pivots on a vertical spindle according to the direction of the wind. Points of the compass may be incorporated as part of the weather vane and these are usually marked by the letters, N.E.S.W. cut out in metal.

The reason why weather vanes were mostly placed on top of churches is because a church was usually the highest point in a rural community and so could be easily seen. Villagers, particularly the farmers could see the direction in which the wind was blowing.

At the top of the spindle a cockerel is often attached. The Hickling Church weather vane is of this design and there is a religious significance for this. The cockerel depicts Peter’s denial of Jesus. Jesus, according to the Bible had warned him that before the cock crew twice, Peter would deny him thrice [Mark 14 v 30]. It was Pope Nicholas 1 [in office 858-867] who ordered that every church in Europe should have a rooster on its steeple to remind the congregation of Jesus’s prophecy. Most churches found it easiest to incorporate the cockerel with their weather vane.

It is not known when the weather vane was first erected on the top of Hickling Church but it has been there for several hundreds of years. Marks on the East side of the tower of Hickling Church shows the roof was originally much steeper. It was lowered because of the thrust pushing the church walls out. At this time the weather vane would have been removed and possibly cleaned before being replaced.

In 2018, money was raised for urgent repair of the weather vane, which cost £2521. This was funded half by events and donations from the community and half from church funds. The company which did the repairs was Lumbard Engineering based in Belper, Derbyshire. Their first task was to take it down and this gave everyone a chance to see it close up. There were many signs to show the weather vane had been used in the past for target practice and as a result had lost its tail. Perhaps this occurred in the 1600’s during the Civil War.

After repair, the weather vane was put once more at the top of the church. Many taking a cursory glance today at the weather vane may not realise that it is no longer in the centre of the roof. When the repaired and cleaned weather vane was reinstalled in the Spring of 2019, it was decided that the roof lead would be unable to support the weight and so a sturdier position was found.

THE CHURCH CLOCK

The church clock was installed in 1885 and since this time has been an important feature in the village especially in the early days for locals to know what time it was. It was paid for by the local farmers so their workers would know when to start and finish work. It was a mechanical clock and had to be wound up 3 times a week. For the last few decades, it was the Bloor family who turned out regularly to ensure that the clock was always wound up and told the correct time.

On 20 June 2017, the clock was cleaned and an automatic mechanism fitted which was paid for from generous donations by the villagers. The cost for this work was £3466.00.

THE CHURCH PORCH AND DOOR

The entrance into Hickling Church is through a porch which like most churches is on the south side of the building. This porch protects the church door and entrance from the elements and in recent years a porch door has been added for further protection.

In medieval days , the porch was a very important place as the baptism service began here and part of the marriage service was held here too. It was also the place where penitent sinners were given forgiveness from their sins before entering the Church.

The stone seats at either side of the Hickling Church Porch were most probably used as a place to carry out civil business. Legal agreements and solemn promises were made there and because it was part of the church, it was a reminder that the agreements were made before God and so must be honoured.

In 2015 members of the congregation decided it would be nice if the porch of the Church could be protected in some way from the elements. Visits were made to several churches in the Southwell Diocese to see what other churches had done. A campaign was made to raise money for an oak framed glass door. Fund raising initiatives included a fete, a mile of pennies and graveyard tours.

John Bloor, the Church Warden and parishioner, Michael Simpson sorted out a design and worked closely with a local company to get the door supplied and fitted. Michael Simpson had worked for many years for Barrett and Swan at Cropwell Butler and once funds were achieved an order was placed with them for the doors. Fitting took place in 2017

HICKLING CHURCHYARD & THE CIVIL WAR

The English Civil War in England started in 1642 when Charles 1 raised his standard on the hill near Nottingham Castle and it lasted until his execution in 1649. The high hill on Hickling Pastures is known as ‘Hickling Standard’, a name dating from this period. Hickling is located on the borders between Royalist and Parliamentarian control. The soldiers and raiders from both sides caused havoc in the village of Hickling. It appears that inhabitants in the area around Hickling had divided loyalties with the conflict splitting families. Perhaps most of the sympathy in Hickling was with the Parliamentarians as Colonel John Hutchinson was the Parliamentarian Commander of Nottingham Castle and nearby Owthorpe was his Estate. He was one of the signatories in 1649 of the death warrant for Charles 1. Colonel Hacker, a Cromwellian, also lived in nearby Stathern Hall, although other members of his family who resided in East Bridgford were Royalists.57 mk

It is known that the Parliamentarians showed no respect for Hickling Churchyard and their horses were tethered here and allowed to trample over graves destroying them. Swords were sharpened on headstones and church walls. Firing practice was done in the churchyard. Is this how the cockerel got its tail damaged?

The Vaux tombstone which today can be seen inside the church near the altar, was mutilated and thrown down in the churchyard during or immediately after the Civil War due to its associations with Catholicism and Royal Power.

Gargoyles and sculptures stone heads had their noses damaged by the Cavaliers.

On the medieval door of the church there are some drilled round holes which have now been filled in. These holes were cut about 3ft from the ground which was a comfortable height for someone kneeling and firing a musket. The intention was to fire through the holes and allowing a safe and easy defence of parishioners who had sought the safety of the Church in the event of an attack.

BURIALS IN HICKLING CHURCHYARD

INTRODUCTION

The Anglo Saxons sometimes buried their dead in wooden coffins but it was not until the early 17th century that the wooden coffin made of flat boards came into general use and has been used ever since. Although nowadays there is a trend for using wicker and more environmentally friendly materials.

Since medieval times the dead have been buried in the sunny, Southern side of the churchyard, with Hickling no exception. The northside which is in the shade, dark and often damp was associated with evil and so was used for those who had met a violent death, were unbaptised, paupers, or strangers in the village.

Throughout the Middle Ages most people were interred only in a shroud, tied top and bottom. They were put straight into the ground. A sprig of rosemary for remembrance or some yew foliage as a symbol of immortality was sometimes also put into the grave. If people could afford it, they were buried inside the church, where hopefully their bones could not be disturbed. The wealthier they were the nearer to the altar they were buried and sometimes a monument erected. Those buried in a village church were usually just buried under the floor and as their bodies decayed, they would give off a terrible strong smell. This is the origin of the well-known saying ‘STINKING RICH’.

Like most churchyards, Hickling burials began one side of the grounds, working across and then starting again. Consequently, in the course of time people were buried on top of one another. When this could no longer happen, a section where the bodies had been busied the longest would be dug up. The bones [having been buried in consecrated ground] could not be thrown away so they would have been gathered up together and put in a crypt or all reburied in one hole. One theory about Hickling’s burial pit is that this was the place where bones had been placed when the churchyard was cleared for new burials. This re-use of the churchyard continued until about 1660.

The place where someone was buried in Hickling Churchyard may have been marked in some way. Perhaps a piece of wood would have been used by the poorer members of the community but this would decay and so nothing remains today of such markers.

Gradually as society changed, tradesmen and farmers in a parish, with not enough money to be buried inside the church itself, felt they wanted a permanent memorial which would not decay or be disturbed. The stone headstones thus came into being. What would these people think today as their headstones have been repositioned into neat lines to make the upkeep of the churchyard easier. At least many of the memorial stones in Hickling Churchyard are in situ and have not been removed completely. Some churches, such as Cotgrave have lifted all the slate stones to make pathways. Other churches have positioned the stones against walls.

Whole families would lay claim to an area in the churchyard for the burial of their family members and this is the reason there is sometimes several graves with the same surname clustered together. The richer members of the community closest to the church building.

In Hickling the stone memorials can be traced back to the late 17th century. Hickling, like many nearby villages, is fortunate in being close to the slate quarries in Swithland, Leicestershire. This slate over the years was used for roofing, cattle troughs, fireplace surrounds etc but from the 1670’s was used also for headstones. With the arrival of the Grantham Canal, transporting heavy slate became easier and the result a profusion of slate headstones in the parishes along its route.

In Hickling Churchyard, it is these older slate headstones which have stood up to the elements. The edges of the letters and the decorations can still be seen and read with ease even though they have been exposed to all kinds of weather during the last 300 years.

Stone memorials are also found in Hickling churchyard and usually these are later stones. Unfortunately, the weather has worn away the lettering on many of these stones making the text unreadable. In 2005, Carol Beadle and Susan Sylke transcribed all the gravestones in Hickling Churchyard so a permanent record could be kept. Since this was done just 20 years ago many of the words on the stone are now unreadable perhaps due to our climate and acid rain. In recent years the slate stones have started also to split vertically from the top.

Granite has become the chosen stone to be used for more modern headstones. There are a few such headstones in Hickling Churchyard.

With this noticeable decline happening to many of the older headstones in Hickling Churchyard, the Hickling History Group have embarked on a project to photograph every gravestone and record the wording on the gravestone. Also, for every person mentioned on a gravestone, their family history and life story has been researched. A map of the churchyard showing the position of all the graves is also being done. Volunteers are always needed to help with this project.

THE BURIAL PIT

In Hickling Churchyard is a section of ground where there is no evidence of graves and this area has been a clear grassed area with no plants or trees as long as people can remember. There are no official records to explain why and unlike many churches, Hickling Church records do not contain a map of early burials in the churchyard.

Early guide books for Hickling Church have reported that this area was the ‘cholera pit’ where people who died from the cholera outbreaks were laid to rest quickly in a mass grave. However. The Parish Records for Hickling do not record many deaths during the major outbreaks in the 1700’s and 1800’s to warrant such a mass grave, so perhaps this story is untrue.

However, evidence does all seem to point to the fact that the area was where several bodies were buried together. Disposal of the bodies of those who had died in the major epidemics of the early modern period undoubtedly presented huge problems.

The Hickling Parish Records and Bishop’s Transcripts records the names of residents who were buried in the churchyard of Hickling. The Parish Records start in 1621 with the earlier documents difficult to read. After 1646, the records appear more complete but with gaps during the Civil War period. There is no section in the Parish Registers which show large numbers of people dying within a short period. Therefore, if this area was the site of a mass grave it is likely to have been dug in the early 1600’s or before.

Another theory is that it could be a ‘plague pit’. A plague pit is the informal term used to refer to mass graves in which victims of the black death were placed. The ‘Black Death’ is thought to be a combination of bubonic, pneumonia and perhaps septicaemia plague, which swept across Britain in the early part of the 1600’s. The plague of the 1600’s in London and the large mass graves within the city are well researched and documented. Parishes throughout the country were faced with a similar problem of how to dispose of the dead quickly

At this period an individual grave was standard, though two or three individuals might share a grave. Traditional funeral practises and internment in which family and friends played an important role in their desire for commemoration came into conflict with the Parish Officers who would have to cope as best as they could with the pressures of burying bodies as quickly as possible. Large pits for communal burials became a critical necessity when the Parish needed a quick burial space for the victims of the plague. The ground was often treated with quicklime and there was generally an understanding that these grave pits should not be disturbed.

The stories of where these ‘plague pits’ were situated in the churchyard was passed down the generations [perhaps with a little embellishment] even though there may be no official documentation. This may be just what happened in Hickling.

There is some evidence that this is a ‘plague pit’ site. Plague was rife in the area around Hickling in the early 1600’s. Existing records seem to indicate that an epidemic of the plague affected one village at a time. In 1609, many hundreds of people died of the plague in the City of Nottingham. The city continued to have outbreaks of the plague during the first half of the 1600’s. In fact, Goose Fair was cancelled in 1646 for fear of it encouraging the further spread of the plague.

Cotgrave, which is not too far from Hickling had outbreaks of the plague in 1616 and 1626 but in the year 1637, the largest one happened between April and September of that year. 93 people out of probably a village population of 450 died that year of the plague. Colston Bassett records show the plague was in the village in 1623 with 83 people dying. The plague reached East Stoke in 1640. Stathern also had to deal with the plague in the early 1600’s with the Hacker family of Stathern Hall losing a child to the plague.

It is also thought that during the Civil War the Parliamentarian soldiers carried the plague from place to place and the Newark outbreaks have been credited to them. A Parliamentarian soldier who was killed in battle at Newark was taken to his home village of Collingham to be buried and a few days later this village had an outbreak of the plague.

Therefore, it can be assumed that the plague may have reached Hickling at some point between 1610 and 1646.

Some of the wealthier families living in Hickling during the later 1500’s left documents which has enabled researchers to understand how the village operated and who lived there. In the late 1500’s, Thomas Noble resided in Hickling and had a large family. He had at least 3 sons, Nicholas, Oliver, John, William and Edward, who would have been Thomas’s heirs and would have had families of their own. This complete family disappear from all records and while it could be expected that one or two of the sons moved away, the whole family would not have done so. Other old Hickling family surnames also disappear at this time including the Hopkinsons and the Hewitts. Were they victims of the plague and buried in a plague pit?

Another theory put forward is that soldiers killed in the Hickling area during the Civil War were buried together in a large pit in the churchyard. There would certainly have been casualties in and around Hickling and these would not have been recorded in the Church records.

In 2024, another possible theory has been put forward. It has been suggested that in the 1600’s the churchyard may have become so full of graves that something had to be done to make room for new burials. Many churches faced this problem and one solution which was adopted was to clear the churchyard. The remains found during this clearance were buried in a large pit within the graveyard and the churchyard was then able to resume the burial of bodies in individual plots once more. Could this have happened in Hickling?

Perhaps in the future more theories will be put forward and more investigations will be made into this section of grassed area in the churchyard. At the moment we can only speculate and perhaps embellish on the theory we think is possibly true !!!

BURIED IN WOOL

In the 1600’s the Wool Industry was the chief source of wealth in Britain and people were encouraged to use it in every way. During the reign of King Charles 11, the decline of this wool industry became very worrying for the Government as so many towns depended on the wool industry for its wealth. The government introduced the ‘BURIAL IN WOOLLEN ACT’ to create a new market for woollen cloth.

In 167 an Act was passed in the interest of the woollen trade ordering all bodies to be buried in woollen under a penalty of 50 shillings with the exceptions of those who died from the plague

It was not easy to carry out this legislation. The wrapping of a corpse in linen was older than Christianity itself and this old custom could not be broken by this Act of Parliament. Therefore, the Government went further and 12 years later passed another Act of Parliament in 1690 to ensure wool was used. This later Act required that within 8 days of a funeral an affidavit to the fact that burial had been in wool had to be brought to the Minister for recording. Failure to do this meant the matter was passed to the Church Warden or Overseer, who would then levy on the defaulting person a large fine. This Act was not repealed until 1812 but had fallen into disuse long before this.

The first burial in wool in Hickling churchyard following the Act of Parliament was the burial of Elizabeth Thurkell on 10 December 1678. The fact she was buried in woollen cloth was recorded in the Parish Records.

A certificate had to be obtained from a magistrate before a woollen burial could take place and records show that the burial of Elizabeth Marriot on 9 November 1679 did not quite run smoothly

‘Elizabeth Marriot on the greens but yed the 9th day of November 1679

I received an affidavit concerning her being buried in woolen within the time permitted under the Act of Parliament. I gave notice by a note in writing under my hand by Mr Stephen Pickard, an overseer of the poor on 17th day of December that no affidavit was brought to me concerning the burial of Elizabeth Marriot in woolen’,

Wool was expensive for some to afford. In Hickling in 1682 the burial of Elizabeth Greasley of the Green in Hickling caused quite a stir. Her family could not afford for her to be buried in wool and the Overseer to the Poor became involved.

BELVOIR ANGEL GRAVESTONES

[As these memorial stones are so unique, a special guidebook dedicated just to Hickling Belvoir Angel Headstones will be produced by Hickling History Group in the near future, so this chapter is just a brief introduction to them]

A type of headstone found in Hickling Churchyard has been given the title ‘BELVOIR ANGEL’. Hickling is fortunate enough to have in its churchyard 34 such headstones which is one of the highest concentrations of these stones in any one graveyard. Although they are known as ‘Belvoir’, the proximity of the stones is not entirely in the actual Vale of Belvoir. Michael Honeybone in his research into these stones concluded that the boundaries for finding them lie to the West by the Fosse Way, at the North as far as Staunton in the Vale, at the North East by the Lincolnshire border and at the South by the villages of Nether and Upper Broughton and Ab Kettleby. The few found elsewhere such as the ones found in Grantham, West Bridgford and Mansfield are rare exceptions.

No one can answer the question as to when they first became known as Belvoir Angel Stones but the name has stuck and is now used in an official capacity.

Belvoir Angel gravestones are usually sandstone or Swithland slate. Their main characteristic is a cherub face [sometimes more than one], with down-turned wings and a ruff around the neck of this cherub. The winged faces were intended to depict the soul of the deceased ascending to heaven

The Belvoir Angel was engraved usually onto slate headstones between 1690 and 1760. Some sources say they were the work of one stonemason. However, as they cover a period of over 70 years this cannot be true, it is more likely they are made by one business in the area. The identity of the engravers will probably never be discovered as none are signed. However, most of the surviving headstones are found around the Hickling area, with 25 in Upper Broughton, 24 in Nether Broughton and 34 in Hickling, it is highly possible the stone were created by craftsmen working in one of these villages. In Hickling, one such stone was found in a garden showing that it has been discarded and re cycled into something else. Also. In Hickling in the late 1700’s there was a family of stonemasons working so perhaps it was this family who created these unusual and interesting stones.

The Belvoir Angel stones are never large or prominent which adds to their charm. Their height varies between 2fr and 3ft.

Between 1680 and 1760, the style of lettering used on standard gravestones changed generally throughout Nottinghamshire. However, the craftsmen who produced the Belvoir Angel headstones were not affected by any change. This further confirms the fact it was just one family/business who was making them. The angels, the layout and lettering all remain basically the same and for this reason they are often called ‘folk art’. Although, skilfully done, the design and layout are almost childlike.

A Belvoir Angel gravestone is generally divided into 3 sections

- The top part – has an angel engraving

- The middle – the details of the departed

- The bottom – an epitaph

The angel has a round face with coil like curls. At each side of the face are triangular wings which point downwards. The wing is in two parts, the feathers nearest the cherub’s face are plump and short. The feathers furthest away are long and taper to the edge of the stone. Some later stones have the angel with a ruff around its neck. It has now been suggested by Mr F Burgess that this ruff represents a shroud.

On the earlier Belvoir Angel monuments, the area around the angel is blank. Later stones have decorations to depict mortality such as skulls, hearts and hourglasses. These decorations often fill the small triangular area in the top left- and right-hand corners of the gravestone. A few stones have text above the cherub’s head either in Latin or English.

The lettering is usually etched into the stone and in some cases can be very ornated. A capital ‘H; may have a diamond shape in the centre of the cross bar of the letter. Sometimes, the capital letters have stylised curls at the end or beginning of the letter, similar to the shape used to express the angel’s curls.

It is not unusual to see a Belvoir Angel stone where the space allocated for the text has run out and so the word is finished above. Also, if a spelling mistake has been engraved, the missing letter merely put above the word. These stones must have taken many hours to engrave and such mistakes rectified in the easiest possible manner. Also, most of the population at this time would have been unable to read anyway!

In Hickling Churchyard, there are Belvoir Angel headstones where instead of engraving into the stone, the stone has been cut away around the lettering. This is called in ‘relief’. These stones are well worth taking a closer glance so as to appreciate the skill and time it would have taken to produce such a work of art. Anne Mann’s gravestone dated 1735 who was the child of George and Mary Mann is one such gravestone.

Many of the epitaphs which appear at the bottom of the design of the Belvoir Angel stone are several lines long. On the stone of Elizabeth Hardy 1728, the verse is 10 lines long and very neatly engraved.

Hickling is fortunate to have such special gravestones in their churchyard but in recent years weathering and age have been taking the toll on them and sadly their condition is deteriorating. Hickling History Group are doing everything possible to preserve the history of Hickling people recorded on these very special stones.

VICTORIAN HEADSTONES

In Victorian times gravestones became more elaborate and commercial. New materials such as marble were introduced, although local craftsmen such as the ones in Hickling continued to use local stone. It was during this time that there was a Gothic Revival in architecture and this was reflected in the style of gravestone. Tombs once found only inside the Church were now placed in the churchyard. They were large and imposing and engraved often with very detailed scenes

Catalogues became available where styles of gravestones could be displayed so the public could choose. The engravers used pattern books and memorial stones appeared in a variety of styles. The individuality of the design by the village stonemason disappeared as memorial headstones now became a commercial product.

Also, during the Victorian era the stonemason’s name or his initials started to appear on the headstone, perhaps a way of advertising for more work.

MODERN HEADSTONES

By the 20th century 3D images appeared. Cherubs and angels which were at one time carved in relief now appeared as life like statues. Hickling churchyard does not have any of these very grand memorials which tend to be seen more in major city and town cemeteries rather than in rural villages. Kerbstones surrounding the grave or family plot with or without a headstone became fashionable. Information was sometimes engraved in the kerbstone itself.

The later headstones are clean cut, often in marble or granite. In Hickling churchyard there are very few such headstones and it remains to this day a place where the headstones are traditional and with conformity.

THE ASHES PLOT

In modern times it has become more fashionable to have bodies cremated rather than buried. After cremation, families are given the remains of their family member in the form of ‘ashes’. These can then be buried or scattered as the family wish. In Hickling Churchyard a section of ground has been allocated for the burial of ashes with place for a small memorial stone. This takes up far less space than a conventional burial. The first person’s ashes to be placed in Hickling was Dorothy Chahal’s mother.