Fields in the Landscape

By Emily Gillott (Notts County Archaeologist)

(Extracts from a talk given at Hickling Village Hall, 22nd September 2023)

“The talk will be about how clues to the past are hiding in plain sight, and in the most seemingly mundane things, all around us. We’ll take a look at how the shape and layout of fields can help us look into the past using maps, aerial photos, and Lidar, all from the cosy comfort of your armchair and laptop. It might also help you see the landscape in a different light when you’re out and about too!”

The images and examples presented during Emily’s talk and her lively style of presentation bring the subject to life in a way that the following notes cannot do; but here is a bit of a skeleton version to whet the appetite:

Palaeolithic (Old Stone Age)/Neolithic (New Stone Age).

‘prehistoric’ can mean Palaeolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic, Bronze Age, Iron Age, Roman and even sometimes Early Medieval. The Palaeolithic covers hominins and can go back over 3 million years. It was in the Neolithic that we started farming, and farming is considered to be one of the defining cultural and technological events of the period. The Neolithic in Britain is from around 4500BC to 2000BC.

This period of history covers almost 3,000 years from the earliest use of stone tools up until about 4,500BC. Over this period people began to shape the landscape around them, instead of simply passing through; for example, to aid hunting/gathering – making a clearing in the trees because it had been noticed that deer gather in such places and they are easier to hunt. Or, clipping back trees makes them fruit better. Footprints were light and movement fluid.

At some unknown point, people began to farm and this was the game changer. To farm, people had to settle in one place or they wouldn’t see the benefit of their labours:

- We begin to see the first evidence of building monuments and burials

- For example, well-preserved sites in Orkney

- The Silbury burial mound (close to Avebury) is contemporary to the Great Pyramid.

- These traces survive, for example, in the Cornish landscape – deeply built stone boundaries (hedges/walls) have remained because they are difficult to move or change but easy to repair. Farmers have continued to work within these ancient boundaries and the small fields and narrow lanes remain characteristic.

The Romans.

The Romans structured their society around Cities. Outside these settlements, villas developed with isolated farmsteads feeding into them.

The Trent Valley was extremely important to the Romans; out-lying colonies such as Britain were used as a ‘bread basket’ to feed the rest of the Empire. They farmed extensively in very neat, compact rectangles of land for export to cities and back to Rome; residents of Rome would have been eating bread made from grain harvested in the Trent Valley. This would have involved wide-scale tree and landscape clearance.

Work in Sherwood Forest using Lidar technology, strips away the trees from the imaging and shows clear rectangles below the surface from Roman farming formations – when the Romans left, the need to export disappeared and such extensive agricultural areas weren’t needed for local self-sufficiency. Many of these areas, like Sherwood Forest, were allowed to grow over again.

Side-by-side mapping.

Some mapping sites allow you to put images side-by-side; it is interesting to put (for example) a Lidar image next to a Google view image of the same location:

- A great site to use for maps is Side by side georeferenced maps viewer – Map images – National Library of Scotland (nls.uk):

Lidar: this imaging technology removes the surface ephemera (trees, hedges, built structures) and shows up what used to be there.

Field markings (visible from aerial maps/images):

- Walls buried below the surface are relatively easy to spot; because they’re a solid, built structure, the soil above it will be relatively shallow and grass or crops won’t grow as well above the buried wall as either side.

- Similarly, ditches are visible because they will have been filled in with relatively softer, less compacted soil with good drainage – crops will grow more successfully.

- Fence post holes can be visible as dotted markings.

Mediaeval:

Once the Romans had gone, communities reverted to self-sufficiency. Villages gradually developed, often clustered around a Manor and a Church (Laxton in Nottinghamshire is a good example to look at).

Cooperation is the key factor.

- A typical village might have 3 large open fields; they were farmed in rotation with one kept fallow (and used for grazing, the animals helping to fertilise it for future cultivation) each year.

- Each open field was divided into strips of land; these were shared out each year so that everyone received a reasonably fair share of good and/or poor land. Everyone would farm different strips each year.

- These strips are often still visible in the landscape; they have a reverse ’S’ bend shape (evolving over time; probably because the plough tipped soil consistently to the left, gradually shifting the line). Known as ‘ridge & furrow’ (locally known as ‘rig and furrow’), remnants are still visible, particularly in areas of undisturbed pastureland.

- Strips were long with a tight headland because this was the most efficient use of a horse and plough.

- Tythe barns would have stood in the centre of the village; all crops were held centrally and shared/allotted (via the Manorial Court?). (You had a garden essentially around your house, where you could grow enough for your household. If you were landless you could make use of the common resources to produce something and then barter and exchange other goods and services. Everyone had tithes to pay to both the Lord and the Church, and these were kept in the tithe barn. The manorial court would deal with allotment of plots, collation of tithes, and any disputes).

- Horses and ploughs etc. were shared or hired amongst villagers or labour might be bartered for the use of equipment.

Typically:

- The village with its Manor and Church would sit in the middle of the settlement.

- The first layer of landscape outside this built area would be made up of open fields and farmed strips.

- Outside these, would be ‘waste’; communal woods and meadows.

- A Main Street would develop through the settlement plus, usually, a back road to support access.

Under this system, people who were too poor to own strips could still subsist. They would have sufficient grounds around their dwelling to have geese and ducks and to grow vegetables. They could forage for wood in communal woods and graze sheep or a cow on the meadows. They could work for other wealthier villagers on their strips or for the Manor or Church.

Everyone is able to contribute to the rural economy and these communities were largely self-sufficient; depending, of course, on how kindly (or otherwise) those in power were.

Enclosure.

Early enclosure tended to be informal; if an individual had money or power, they might say – actually, I don’t want to change strips every year, I’d like to keep these ones and build a hedge or a wall, now it’s mine – keep off!

- Car Colston was common land and has been preserved by modern ‘open access’ legislation but it is a rare enclosure survivor.

In 1750 Enclosure was enforced by an Act of Parliament – for the common good. It was extremely unpopular but because informal enclosure was already happening, Parliament decided it should be formalised – just had to be done, not doing it was worse.

Someone living 400 years ago wouldn’t recognise our landscape. Enclosure introduced the modern concepts of ‘ownership’ and ‘keep out’ – the idea of ‘don’t go through my garden’ etc would have been quite alien. Pre-enclosure, anyone could go anywhere and collect/share as needed (There were still rules, but they were common rights that were managed collectively rather than a top-down exclusive approach. Some places were still private, but exclusion from the landscape was the exception rather than the rule. The exception was the closed-off deer parks but there was no need to poach in the Lord of the Manor’s deer park because you had access to the local woods and you could hunt there, instead. (Deer parks were unpopular because they employed ‘deer leaps’ that allowed deer to jump the fence into the park, but they couldn’t jump out again. So some people saw those deer as fair game as they had been collected by the owner of the park to the detriment of the game available to the many).

Enclosure was intended to be fair in allocation; however, the cost of enclosing your allocated strips fell to the new owner which disproportionately affected the smaller landowners. If you’re rich and have a big area to enclose it’s relatively cheaper than enclosing a small area. Many who were allocated small strips couldn’t afford to put boundaries in place (often thorn hedging) and they gave up their allocation, selling it to others who could afford it. These people are then displaced/disenfranchised; they can continue to work within the rural community or they fled to the cities.

All of the land around the settlement was ‘enclosed’. This meant that the ‘commoner’ no longer had access to communal grazing or the communal woods surrounding the village; they lost all their rights of foraging and grazing and could no longer subsist – their options were stark:

- Flee to the city

- Starve

- Work for the landowner class

‘Wasteland’: under the mediaeval system, wasteland referred to the meadows and forest around the settlement which wasn’t being strip-farmed/open-field system – it was often good quality grazing and valuable for foraging. It certainly wasn’t ‘useless’. Enclosure defined wasteland as useless/low-grade and it was enclosed/allocated with all common rights lost.

- A reference found in Hickling relates to ‘wasteland belonging to the Manor’; a small triangle of wasteland was given for the building of the village school in 1836 and three dilapidated (but occupied) cottages were taken down to make way for it. (These cottages had probably once been built by or for the rural poor)

Social consequences of Enclosure:

Enclosure and the Industrial Revolution went hand-in-hand.

- There was a massive population movement to the cities with people living in slums and in poverty – a workforce feeding the new factories and technologies.

- However, these cities needed to be fed – rural workers had been lost to the cities and new steam farm machinery improved efficiency. These early steam engines needed more regular fields and the landscape began to change shape again.

- The Church and the Parish now had to take active responsibility for the new rural poor and make provision for them; they were no longer able to be self-sufficient.

- Parishes had to look after their ‘poor’; the poor box in the Church, committees made up of members of the community to allocate help and support, legacies in Wills to provide fuel or bread at festival times.

- Allotments were allocated within villages to support self-sufficiency; many modern allotments show signs of survival from this period. For example, wide verges with apparent boundary markings. (Insert Hickling allotments – how far back do they go?)

- Cottages would have begun appearing with small pieces of land for home-growing.

- Some villages set aside allocated areas for the settlement of the poor; Little Lunnon in Scarrington is an example of this which survived late into the C20th. Whenever you come across ‘Little London’ or ‘Little Lunnon’ as a place name it will date back to these poor relief areas – the source of the name is unknown, perhaps ironic? (insert EP news article scan)

And finally (some snippets):

The talk ended with reflections on where we are now; whether we can learn anything from the mediaeval systems and the problems of Enclosure (problems which we are still seeking solutions to). As a nation we are trying to feed our biggest ever population and we are facing the consequences of climate change – we’re putting solar farms on productive farmland; vertical farming; land efficiency. We removed hedges for big prairie farming but now find that the big machinery can cope with smaller fields after all and we need to restore biodiversity to the landscape. (The big fields saw a huge increase in soil erosion and loss of soil quality, hence why so many schemes currently seek to reinstate them.) The National Trust are experimenting with strip farming again – mixed crops for pest control, soil management and productivity. (Return of strip-field farming creates haven for rare species in south Wales | Conservation | The Guardian)

Extra notes:

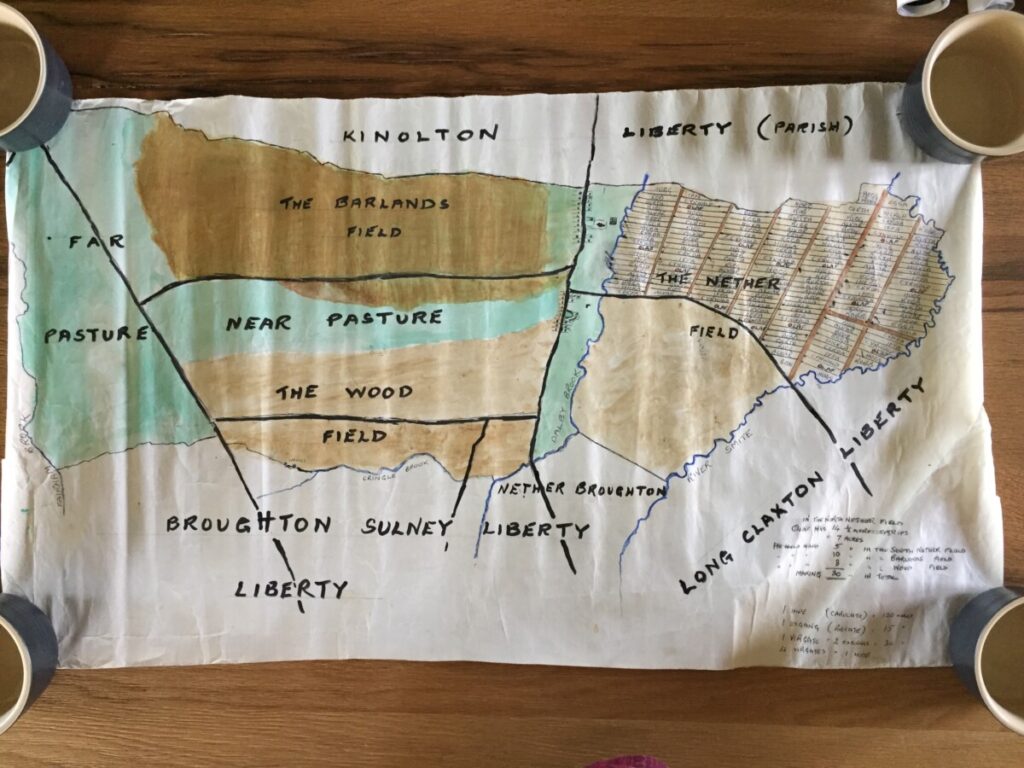

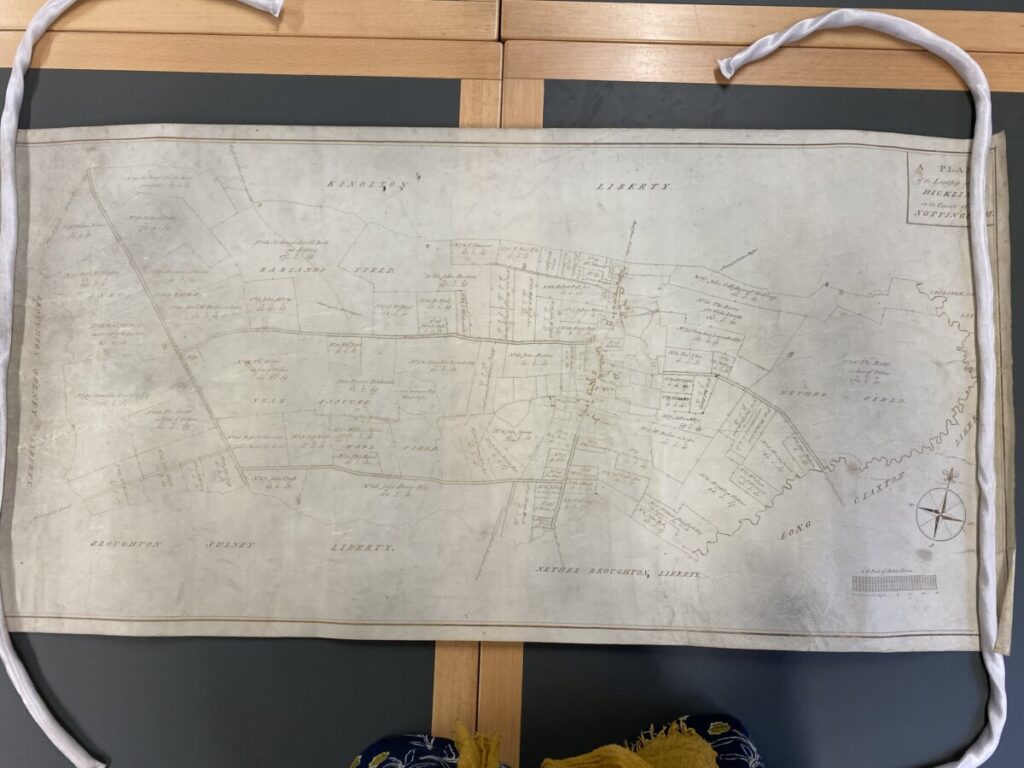

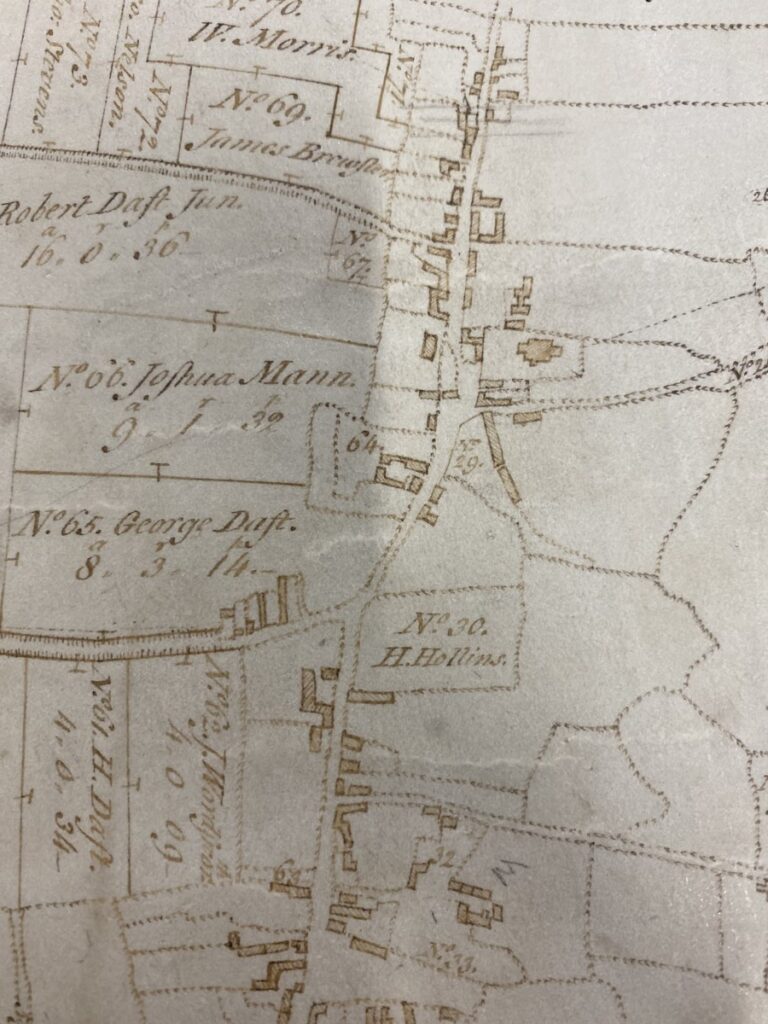

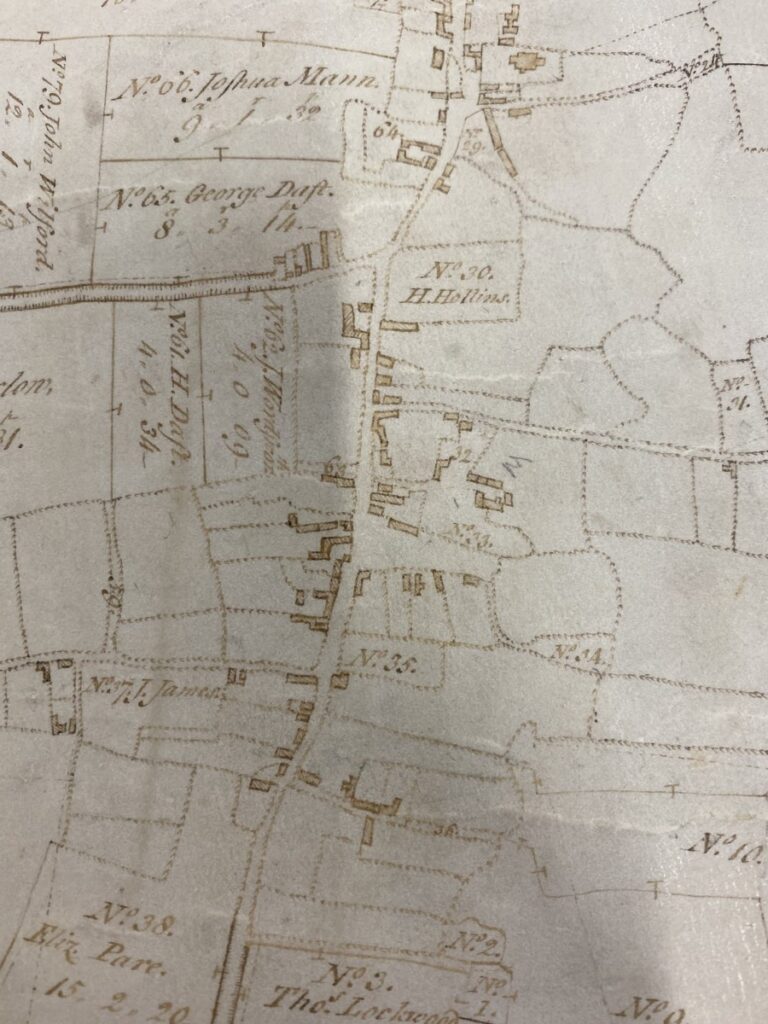

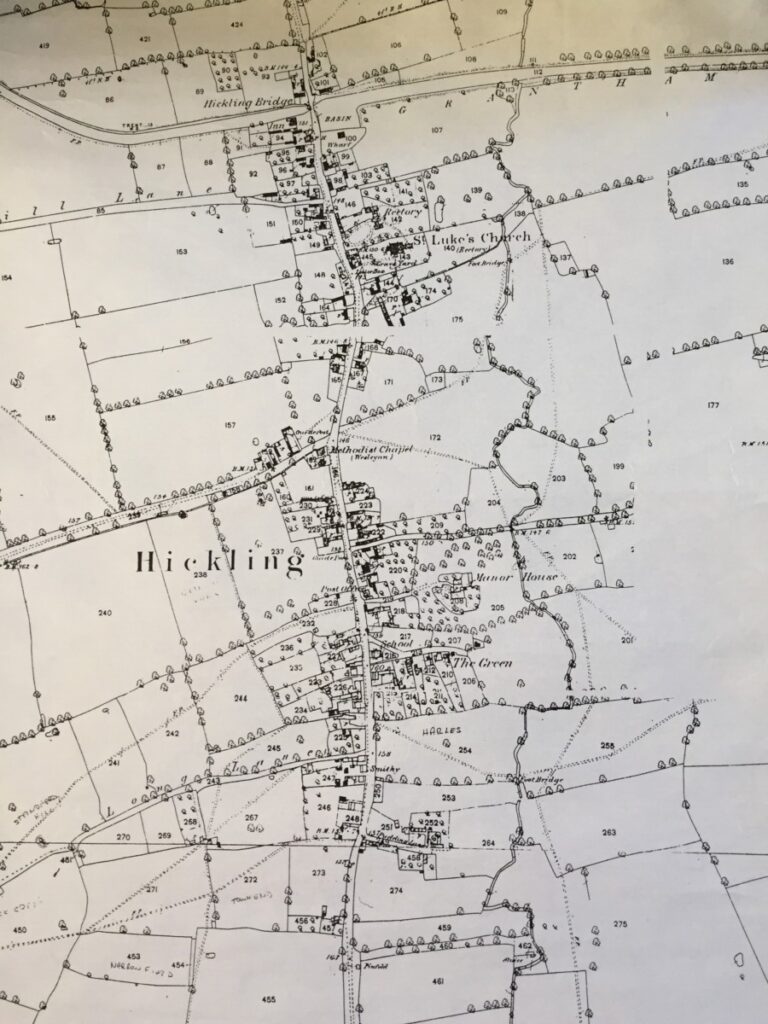

- The Enclosure of Hickling is dated 1774; we are fortunate that both the Enclosure Map and the Enclosure Schedule (a written record of every transaction) have survived. Work to transcribe the Schedule is ongoing.

- Further resources that we hope to find: Manorial Records and Tythe Records (we don’t know, as yet, whether these have survived for Hickling).

- The Rutland and Northamptonshire poet, John Clare, was a farm labourer and renowned nature poet. His writings covered the period of Enclosure and the changes in his beloved landscape. Sadly, he ended his life in an Asylum where he continued to write about nature and his deep sense of loss.

The Story of Where You Live, edited John Andrews:

- (The Manor 1066-1550) … A Lord of the Manor also owned the right to mine coal, iron and other minerals on his manor. (…) Along with these rights came luxuries that only the very privileged were allowed such as a rabbit warren, dovecote and fish ponds. These were a valuable source of food for the lord and his household. The local court of law: Each manor held a court to resolve disputes between tenants, punish those who had broken local rules and decide on farming practices. The court was presided over by the lord’s steward or bailiff but run by 12 jurors, or ‘homagers’, chosen by the tenants. These jurors made decisions on matters such as whether to restrict the number of cattle that could be grazed, how much to fine someone who hadn’t muzzled a dog, or what to do about blocked drains. They also elected the officers for the coming year, such as the constable (who enforced law and order), the pinder (who rounded up stray animals), and the ale-taster (who tested the strength of a brew). Manor courts continued to flourish well into the C16th and C17th and some, such as the manor court of Laxton in Nottinghamshire, still operate today.

- By 1900 only one in ten adults worked in agriculture, compared with seven out of ten at the start of the 19th century.

The Making of the British Landscape by Francis Pryor, 2010 (Extracts)

The chapter headings in Francis Pryor’s book offer a neat summary of the timeline of landscape change in Britain:

- Britain after the Ages of Ice (10,000-4500BC)

- The First Farmers (4500-2500BC)

- The Making of the Landscape: The Bronze Age (2500-800BC)

- The Rise of Celtic Culture: The Iron Age (800BC-AD43)

- Enter a Few Romans (AD43-410)

- New Light on ‘Dark Age’ and Saxon Landscapes (AD410-800)

- The Viking Age (800-1066)

- Steady Growth: Landscapes Before the Black Death (1066-1350)

- The Rise of the Individual: The Black Death and Its Aftermath (1350-1550)

- Productive and Polite: Rural Landscapes in Early Modern Times (1550-1750)

- From Plague to Prosperity: Townscapes in Early Modern Times (1550-1800)

- Rural Rides: The Countryside in Modern Times (1750-1900)

- Dark Satanic Mills? Townscapes in Modern Times (1750-1900)

- The Planner Triumphant: Landscapes in the Late Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries.

- Sat Nav Britain: What Future for the Landscape?

The Making of the British Landscape by Francis Pryor, 2010 – Chapter 7, The Viking Age, A New Way of Organizing Farms: Open Fields:

In the later Saxon period there was a widespread movement in parts of north-eastern, central, Midland and southern England to gather together dispersed farmsteads to form larger, more concentrated, or nucleated settlements. These settlements and the Open Fields around them together formed the ‘Champion’ landscapes so characteristic of the early Middle Ages. Incidentally, the word ‘champion’ derives from the Low Latin campania and the French champagne meaning farmed countryside, as opposed to woodland. The purpose of the system was to exploit arable farmland efficiently, employing communal tools and labour, and using animals and their manure to restore the fertility of the land. It only worked because labour was increasingly plentiful in later Saxon times and in the first half of the Middle Ages.

The houses of the men who worked the fields were grouped into a village, which was surrounded by two or three large Open Fields which were worked by the inhabitants of the village. The peasant farmers of the village owned strips of land in the Open Fields which were marked out on the ground. Every strip within each open field had to be worked in the same way. Thus one strip could not be left fallow, and another allowed to grow a crop of, say, wheat. Much of the land was owned by the local landowner who usually resided in the manor house, where the manorial court met to decide which of the Open Fields were to be cropped and which to be left fallow (unploughed). Some of the peasant farmers paid for the use of their strips with labour. After perhaps two years of cropping, the land was left fallow (unploughed) for a year and animals were allowed to graze it. The manorial court also sorted out disputes over landholdings, tenancy agreements and matters relating to the supply of labour.

The Champion system only worked in certain areas. In wet or hilly regions, where ploughing was difficult, or in areas where the soil was simply not suitable, the older patterns of farming persisted. These regions sometimes, but not always, included large areas of woodland, which is why non-Champion farmed landscapes are often referred to as woodland landscapes. Woodland landscapes are very variable. In some areas individual landholdings are small, in others they were large. Sometimes sheep dominated, other times it was cattle. Grazing, fodder production, and of course woodland produce such as firewood and coppice products wereusually important in woodland landscapes.

The contrast between Champion and woodland landscapes has been described as ‘planned’ versus ‘ancient’. However, this twofold division is very broad indeed and is probably only useful when used to describe or define the planned. Champion areas of central-southern Britain with their clearly defined large villages within regularly laid out rectangular fields, isolated blocks of woodland and large farms. The woodland areas are far more diverse: some have blocks of woodland, others huge spreads of open or scrubby woodland, yet others have little woodland at all; most feature smaller farms and favour pasture over arable, but again, not always. Villages in woodland areas tend to be smaller, or less well defined; but there are of course exceptions to this rule.

The Making of the British Landscape by Francis Pryor, 2010.

Glossary.

Assart: In mediaeval times assarts were clearings around the edges of woods or heaths which usually held a farmstead or small holding.

Breck or Break: A piece of steep or rough land often found between good arable ground, which could be taken into cultivation from time to time.

Bronze Age: The period characterized by the introduction of bronze, an alloy of copper with tin. It saw the construction of numerous henge monuments and round barrows and was followed by the Iron Age around 800BC.

Burgage or burgage plots: The urban equivalents of ‘tofts’ in the Middle Ages.

Champion landscapes*: A medieval farming system based around collective holdings in which peasant farmers held strips within large ‘Open Fields’. The ‘classic’ Champion landscapes are on the heavier clay soils of the Midlands.

Cruck: A large curved beam which ran from the floor to the roof in many medieval houses and barns. They were often formed from the trunks of black poplar, a native tree which in windy areas grows naturally in a gentle curve.

Enclosure: The process whereby land held by several people, whether as strips in ‘open fields’, as commons, shared heath, upland or meadow pasture, was taken into the control or possession of a single individual or estate. Enclosure was either voluntary (‘by agreement’) or statutory (by Act of Parliament).

Iron Age: It followed the Bronze Age, around 800BC, and was the period when iron came into common use. It saw the full development of the British landscape, including the construction of hundreds of hillforts. In southern Britain it ended with the Roman conquest of AD43.

Medieval: The period that covers all history from the end of Roman times until the Reformation of the mid-sixteenth century. It is generally divided into two; early medieval (from the fifth to the eleventh centuries) and late medieval, the equivalent of the ‘Middle Ages’, as defined here.

Mesolithic or Middle Stone Age: The period between the Upper Palaeolithic and the Neolithic from about 8000BC to 4500BC. It is characterised by hunters and gatherers who made tools and weapons from small flints known as microliths.

Middle Ages: Here the term is used to define the latter part of the medieval period, from the Norman Conquest (1066) until 1550. It is divided into two approximate halves: early (1066 to 1350) and late (1350 to 1550).

Neolithic or New Stone Age: The period between the Mesolithic and the Bronze Age. The Neolithic saw the introduction of farming and the construction of the first large communal monuments, such as long barrows. It spanned the period 4500-2500BC.

Nucleation*: A process of the late Saxon period and the early Middle Ages in which a number of dispersed farmsteads in lowland Scotland and central England came together to form tighter communities in central villages; these often developed into Open Field and run-rigg farms (Scotland).

Open Field landscapes*: Open Field farms were organsied around parishes and manors in the Middle Ages and many continued into post-medieval times. It was a form of communal farming where peasant farmers worked individual strips which were held in two to four large Open Fields – so named because the strips within them were open and never fenced, hedged or ditched.

Palaeolithic or Old Stone Age: The first and longest period in British prehistory. The earliest inhabitants of what was later to become the island of Britain settled around 600,000 years ago. The Palaeolithic (or Upper Palaeolithic) ends with the retreat of the Ice Age ice, around 8000BC.

Planned Landscapes: Landscapes of larger regular rectangular fields, straight roads and large villages. These usually developed from Champion and Open Field systems in the Middle Ages, often, but not always, as a result of Parliamentary Enclosure.

Plantation Towns: These are sometimes known as medieval new towns. They were mostly planted in the landscape by order of the Norman kings from the eleventh to the thirteenth centuries, but later examples can also be found.

Post-Medieval: The period that follows the Middle Ages. It can be used to describe the entire span of time between 1550 and the present, or it can be subdivided into early modern (1550-1750) and modern (1750 – the present).

Ridge-and-furrow: A method of farming in which repeated ploughing in the same direction causes the build up of high ridges, separated by deep furrows. Although characteristic of Champion landscapes, ridge-and-furrow is also commonly found in areas with poor surface drainage.

Roman and Romano-British: The term Roman is used to define the period when large parts of Britain were in the Roman Empire (AD43 – 420). The term Romano-British describes the people and the culture at the time, thus: villas were constructed by Romano-British citizens in Roman times.

Saxon*: The term used to describe post-Roman and early medieval times in England (410 – 1066). The eastern Scottish equivalent is Pictish. The period saw the reintroduction of towns and the development of the Open Field system.

Toft: A plot of land that accompanied a house in a medieval village. In Open Field villages tofts did not form part of the co-operative system and provided the occupants of the house with grazing and/or produce, such as fruit and vegetables.

Upper Palaeolithic: The final phase of the palaeolithic marked by the appearance of modern humans (Homo sapiens), from about 40,000 years ago. It was succeeded by the Mesolithic around 8000BC. Flint tools of the period were far smaller than those used previously.

Woodland or ancient landscapes: These landscapes of winding lanes, hamlets and small irregular fields grew from ancient patterns of individual farmsteads in areas where nucleation and the Open Field system did not develop. Ancient or woodland landscapes were believed to have survived because the climate was wet, or the soils were not suited for intensive arable, but we now realise that social factors were also crucially important.