Hickling has a rich history in the Anglo-Saxon/Viking period and we were fortunate to host a lecture on this period in early 2019 by local author, Rebecca Gregory.

A more detailed exploration of the Anglo-Saxon/Viking history of the Church, including surviving monuments and explanations of the terminology can be found on the pages relating to the Anglo-Saxon/Anglo-Scandinavian Coffin lid and the Tree of Life sculpture.

We are very grateful to Rebecca for putting together a blog/article for the website; for further information, her book is a great place to start: click on the book cover image to buy a copy.

Both books are available from 5 Leaves Publishing: click here or by clicking on the front cover images.

Rebecca Gregory: Viking Nottinghamshire (blog post)

The first impact of the Vikings on England was as seafaring raiders, targeting churches and monasteries around the coast from the late eighth century. This had little impact on inland areas, however, and it was only when the so-called “Great Heathen Army” began their conquest of England in the year 865. This army was made up of many groups of warriors from Scandinavia and elsewhere, banded together under shared leadership, and with different aims from the piratical raiders who had targeted the coast in previous decades. This army began its travels in East Anglia, then marauded round much of eastern England, spending winters in encampments in Nottingham, Repton (Derbyshire), Torksey and Foremark (Lincolnshire), among others.

Recent excavations at Repton, Torksey and Foremark have given us a picture of who the Great Heathen Army may have been. They probably numbered several thousand people, including women, children, craftspeople and traders, and they left behind them evidence of leisure activities as well as industry and warfare.

After their campaign was over, a peace treaty was struck with the Anglo-Saxon leadership, and a portion of England was given over to Viking rule from the year 878. This area would be known as the “Danelaw”, and stretched from London to the Mersey, incorporating the areas that would become Bedfordshire, Buckinghamshire, Cambridgeshire, Derbyshire, Essex, Hertfordshire, Huntingdonshire, Leicestershire, Lincolnshire, Middlesex, Norfolk, Northamptonshire, Nottinghamshire, Suffolk, and Yorkshire. These are the counties, therefore, where many Scandinavians settled in the late medieval period and left their mark on place-names, dialect, archaeological evidence, and regional identity.

Place-names are one of the most abundant sources of evidence for medieval settlement and language. While Hickling has an Anglo-Saxon name, there are several settlements nearby which have names containing words from Old Norse, the language of the Vikings. Owthorpe is ‘Ufi’s outlying settlement’, from a Viking man’s name; Long Clawson is ‘Klakkr’s settlement’, again containing a Viking man’s name; and the various nearby places ending in –by come from an Old Norse word for a settlement. While place-names don’t provide a reliable indicator of exactly who lived in those places, they demonstrate that the language of the Vikings was in general currency in the local area.

In the years after the Danelaw was reclaimed by the Anglo-Saxons in the tenth century, Viking influence did not simply disappear. This period in history is best called the “Anglo-Scandinavian” period, where the two cultures, languages and traditions combined to make new forms of cultural expression and identity.

Hickling contains a very special example of Anglo-Scandinavian identity: its “hogback” stone, which can be found inside St Luke’s church. Hogback stones were originally grave covers, and are found only in areas of England where Scandinavians are known to have settled. They contain mixtures of newer Christian iconography and traditional Scandinavian-style designs, and are a clear expression of Anglo-Scandinavian identity.

For more about the Viking history of the East Midlands, you can access a plethora of resources, including blog posts, lectures, and information on artefacts and names, at emidsvikings.ac.uk. The Key to English Place-Names (kepn.nottingham.ac.uk) provides the origins of most settlement-names in England, with the exception of some smaller villages and hamlets. You can find more on all the topics touched on above in my book, Viking Nottinghamshire.

(Rebecca Gregory Sept 2019)

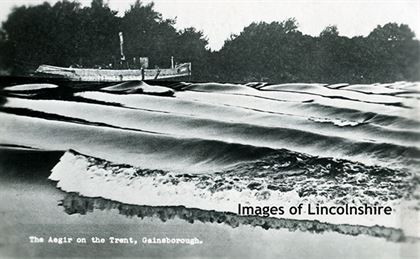

The Trent Bore/Aegir

Canal & River Trust; Waterfront article by Abigail Whyte:

It’s early morning in the year 867AD; a Viking Chieftain is venturing up the River Trent towards Nottingham, leading a small fleet of longboats, when he hears a slow rumbling noise behind him. He peers over his shoulder and catches sight of a faint ripple on the water in the distance, slowly growing bigger as it comes towards him, the edges sloshing up the muddy banks. He and his fellow comrades row as hard as they can but there’s no escaping the invisible leviathan as it lifts his craft and surges past him, leaving a trail of small waves and a band of bewildered Vikings in its wake.

Back then it would have been easy to believe this phenomenon was the wrath of a Norse God, but today we know it as a tidal bore – the Trent Aegir – believed to have been named after the king of the sea in Norse mythology. Some believe the name to derive from the Latin word augarium, meaning ‘omen’ or ‘prophecy’, while others think it derives from the French eau guerre or ‘water war’ for the way the wave travels up the river like a wall of water.

Despite manmade constraints such as weirs and dredging lessening its power, the Aegir is still an unstoppable force of nature. It occurs on the lower tidal reaches of the Trent when a high spring tide from the Humber estuary meets the downstream flow of the river. The funnel shape of the river mouth exaggerates the effect, causing a tidal wave of up to 1.5m to travel as far as Gainsborough at around 10mph.

High tides occur during full moon or new moon phases, when the gravitational force of both the sun and moon reinforce one another. Large annual tides occur around the Spring Equinox in March and Autumn Equinox in September, reinforced by full or new moon phases, creating the highest bore waves.Top fact: Some sources claim that it was here, on the banks of the River Trent at Gainsborough, that King Canute performed his intentionally unsuccessful attempt at turning the tide. In order to prove to his sycophantic courtiers that he didn’t have divine powers, the 11th-century king commanded the oncoming bore to halt and ended up with rather wet legs.

https://canalrivertrustwaterfront.org.uk/history/the-trent-aegir/

Anglo-Saxon Period

(by C Beadle)

ANGLO-SAXON Settlements developed just off the main Roman Roads. Hickling Village was one such early Saxon village as it is believed Upper Broughton was, too.

The ridge and furrow land forms found in this area date as far back as this period and before as the farmers ploughed the vast open spaces without any enclosures (more about ridge and furrow under agriculture).

Anglo-Saxon Burials

Anglo-Saxon ‘temples’ were typically found on a hill top.

A Hickling Pastures farmer found some stone troughs which are believed to be Saxon coffins – these are now used as flower troughs by a local resident. However, plans are being made to have these specially investigated to confirm their age, origin and use.

In 1969, Malcolm Dean conducted rescue excavations ahead of the construction of a bridge over the Fosse Way north of the nearby Roman Town. This recovered over 100 Anglo Saxon inhumations, although no attempt was made to establish the boundaries of the cemetery. Sadly, Dean died soon after and the excavation report was not published until 1993, thanks to the rescue efforts of Gavin Kinsley.

Hickling Church has the oldest Church Monument in the County of Nottinghamshire (‘Top Trumps’ Heritage, Southwell Diocese)

As Arthur Mee wrote: ‘The oldest treasure and one of the finest things of its kind in the land, is a relic of a 1000 year old tomb. The coped cover of a Saxon Coffin. It is 5ft 6in long, showing in its mass of carving a fine cross and animals enmeshed in interlacing knotwork. An animal at one end is biting on its own tail.’ (in Hickling Church, ref. The King’s England Nottinghamshire, Mee).

This stone was inspected in 1888 by Rev. G.H. Browne BD who was the Disney Professor of Archaeology at Cambridge University. He reported; ‘At Hickling you have the lid of a sarcophagus which is the most perfect and valuable pre-Norman work of the kind in England …. as a sarcophagus with other than Christian subjects it is quite unrivalled.’

In a letter to the Rector of Hickling from the Bishop of Bristol dated 10th December 1906; ‘The bar which forms the ridge piece, and the stem of the very pretty cross, passes out of the snout of a bear at each end. The bear clutches the stone with its fine paws. This is a Scandinavian survival from the practice of casting a bear skin over the body of a warrior. It is a feature of the Anglo-Saxon [Scandinavian] ‘hog-back’ stones of which there are many in Yorkshire. Yours is at least a very unusual application of it to a flat gravestone.’

From the Southwell Diocese booklet, ‘Top Trumps’; ‘Hickling boasts the earliest monument – a coped coffin lid with mid-10th century interface, a cross and two bears’ heads. It formerly lay in the Churchyard but has now been brought inside.’

Further Reading: ‘The Church in Anglo-Saxon Society’ J.Blair 2006