In 1880 George Simpson, who was born in Cotgrave, married Sarah Ann Brewin, born in Shoby. They moved to Kinoulton, where four children were born, and then in 1886 or 1887 to Hickling, where they had another four. George was then a butcher and grazier living at Rose Cottage on Main Street.

The children were:

- Ida, born 6 September 1881

- Charles (Charlie) born about 1883

- Albert born 15 August 1884

- Lily born 1886

- Cecil born 1888

- Donald (Donnie) born 8 January 1890

- Rowland (Rowley) born about 1891

- Emily (Emmie) born 26 November 1892

In 1908 George went with his son Cecil on his butcher’s round with his cart, visiting Kinoulton, Owthorpe and Cotgrave. At the last place he stopped for tea with his mother and died there, aged 48, of a stroke. Sarah Ann marked the anniversary of his death in the In Memoriam column of the Grantham Journal every year until she died.

Sarah Ann continued to run the business with the help of those of her sons living at home. Albert was married in 1907 and in 1912 Rowley emigrated to New Zealand. With the onset of war the sons remaining at home all joined the forces and so Sarah had to sell her beast and some of her land. She instead took in paying guests and also served teas, a busy venture since Hickling was a popular holiday destination in the summer.

Charlie followed his father’s profession of butcher, in 1901 living and working with his mother and in 1911 living with butcher Thomas Jackson of Long Clawson and working as his assistant.. He also worked at Frisby, Skegness and Melton Mowbray.

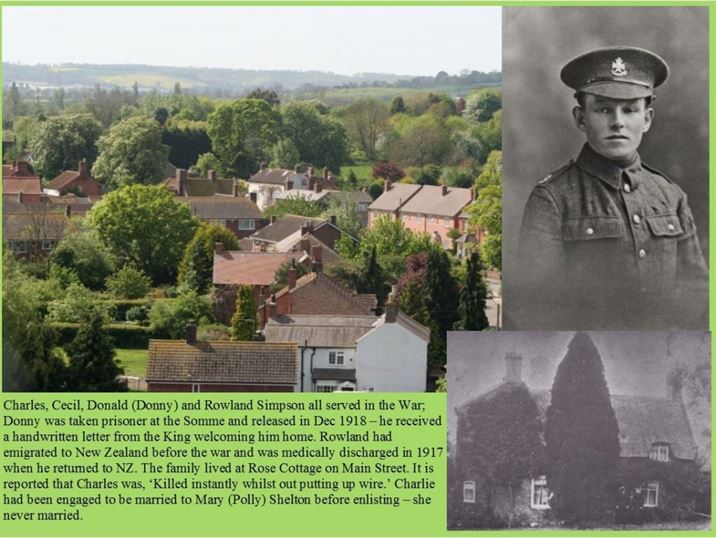

He enlisted on 9 August 1915 and, like his brother Cecil, joined the Notts and Derby regiment and later transferred to the Yorkshire Hussars, Alexandra Princess of Wales’ Own. He trained in Woking and then went abroad with the British Expeditionary Force. In October 1916 it was reported that he had been promoted to Lance Corporal. In May 1917 he returned home on leave, rejoining his regiment on the Somme in June.

On 11 July 1917 Charlie had the job of putting up wire during the night. He was killed instantaneously by a shell but his body was recovered and finally interred in the Fins New British Cemetery. Letters to Sarah Ann reporting on the death were dated 12 July and referred to his death as having been “last night” and it is probably for this reason that the date of his death as recorded on the memorials in Hickling is 11 July. It is perhaps because it was a night time operation that some confusion arises, because the “official” date of his death is 12 July and that is what is written on his headstone. He was 34 years old.

Sarah Ann first heard the news on 16 July, when she received a letter from Charlie’s great friend Sniper T Foster. A few days later she also received letters from his Captain, his Sergeant and the Chaplain who buried him. There must have been some comfort to hear that his death was instantaneous, that he was with those close to him when he died and that his body was recovered.

This is the letter from his Captain: Dear Mrs Simpson, – It is with deep regret that I have to inform you of the death of your son, No 29488 Lance-Corpl. C Simpson. He was killed instantaneously whilst out putting up wire last night. His death will leave a very big gap in the Company, as he was a big favourite with officers and men. Again assuring you of our deepest sympathy with you in this great bereavement, I am, yours very sincerely, FA Mansfield, Captain, 12/7/17.

His Sergeant wrote: Dear Madam, – I am writing on behalf of the boys of my Platoon to express their profound sympathy in the loss of your son Charlie, which occurred last night, whilst in action. He was extremely well liked by his comrades; his cheery disposition and his zealous sense of duty endeared him to all he came in contact with. I can assure you that the Platoon will miss him greatly. The nature of so personal a loss is hard to bear, but his reward will be great, your loss will be his gain. Your consolation must be the same as thousands of other mothers has been – that he laid down his life to keep the ‘old flag flying’. I was with him myself at the time of his death, and I can assure you that he suffered no pain. His death was instantaneous. I trust this letter reaches you, in which is confined the deepest sympathy of all. Yours truly, Sergt Albert Ratcliffe and the Boys of the Platoon. PS – It will be a consolation to you to know he will be buried in a soldier’s grave behind the lines. 12/7/17.

Sarah Ann gave instructions for the inscription “Gone but never forgotten” to be inscribed on Charlie’s gravestone.

The flag was flown at half-mast at the village school in tribute to a former scholar. Although the Simpsons were Methodists both the church and the chapel marked Charlie’s death in their Sunday services. In addition to leaving a mother and seven siblings, Charlie also left a fiancée, Pollie Shelton. Pollie never married .

Each year Sarah Ann put an anniversary In Memoriam for Charlie in the Grantham Journal. So too, for many years, did Pollie, her chosen words being “Thoughts return to days long past, Years roll on, but memories last”.

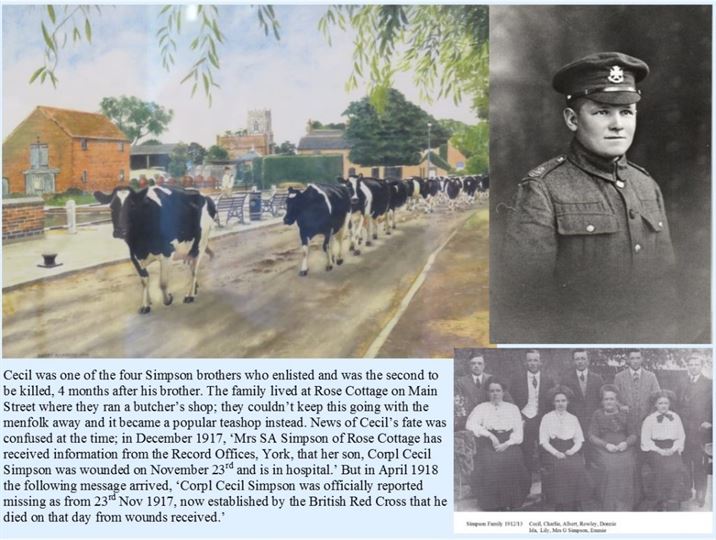

Like Charlie, Cecil followed in his father’s profession of butcher. In 1911 he was living in the house of a butcher and grazier in Skegness, one of six assistant butchers in the household, in addition to which there were two apprentice butchers. He also worked in Melton Mowbray, Barnsley and Loughborough.

Also like Charlie, Cecil joined the Notts and Derby regiment and then transferred to the Yorkshire Hussars, Alexandra Princess of Wales’ Own. In October 1916 it was announced in the Grantham Journal that he had been promoted to Sergeant. This may, however, have been a mistake because Cecil was in fact a Corporal when he died.

In December 1917, about five months after Charlie had been killed and not long after Sarah Ann heard that Rowley had been discharged from the army as medically unfit, she heard that Cecil was wounded on 23 November and was now in hospital. Further enquiries were made by the British Red Cross and letters from colleagues also helped to give a more detailed account, which was reported the following April. Sergeant Albert Ratcliffe, the same person who had written to Sarah Ann and said that he had been with Charlie when he died, said that Cecil had been wounded in the attack on Bourlon Wood, part of the first Battle of Cambrai. Sergeant Ratcliffe was wounded ten minutes later and, being unable to bandage either himself or Cecil, he crawled to the stretcher bearers where he was attended to and taken to a dressing station. After that he was not certain what had happened to Cecil. Corporal Galloway believed that Cecil had died and was buried where he fell. The conclusion of the enquiries was that Cecil died on 23 November from the wounds received. It was said that Cecil was much respected by his colleagues and a universal favourite. He was 29 years old.

By this time Donnie was also missing in action, it being feared that he was a prisoner.

The death notice posted in the Grantham Journal by his mother finished: “Greater love hath no man than this – he nobly and bravely gave his life, so full of promise, that others might live”.

Having no known grave, Cecil is commemorated on the Cambrai memorial.

The Simpsons were prominent members of the Methodist chapel in Hickling and were also active in many other areas of village life. Even the shop window was brought into play, with it being used to show off a cup that the cricket team had won on one occasion, and the wedding gifts of the former post mistress on another! Many members of the family were also musical – their father George had been extremely fond of music. Sarah Ann was very observant of Sunday; when the first Sunday newspaper came to the village she ordered a copy thinking it was a religious paper – she immediately cancelled her order when she realised that this was not the case. Likewise, she would not serve teas to paying guests on a Sunday. No beer was allowed in the house, although her granddaughter Maggie recalled that during the latter part of her life she allowed the men to have a beer with their meal at hay-making time. At least one gospel mission service was held in her home field and an evangelist held open air meetings on her land. Sarah Ann was also a staunch Liberal and one of the rooms at Rose Cottage was used as the Liberal Committee Room at election time. She was a great admirer of Lloyd George and had his picture in a prominent position, as well as one of Gladstone. Sarah Ann died in 1930, age 74.

Ida married Ernest H Shelton, who had been widowed in the previous year, in 1931. She was 49 and he was about 60. She died in 1956 aged 75.

Albert took on a variety of roles in organisations in the village. He was secretary of the Men’s Guild, the Rural Worker’s Approved Society for Health Insurance and the cricket club; he was one of three people organising a social evening aimed at raising funds to pay off the debt on the causeway fund; he led the carol singers; he was a member of the Peace Celebration Committee; he was MC at social events in aid of the Parish Clock fund and the village contribution to the Belvoir Nursing Association and he served as a referee for boys’ football. He also played in the village billiards team. In 1907 he married former Nottingham teacher Elvenus (Venie) Pullen. Unusually for the family, Albert was a member of the church and the wedding was held there. This does not, however, seem to have caused any problems because Lily and Emmie were bridesmaids, Charlie was best man and Sarah Ann entertained friends and family afterwards at Rose Cottage. The couple moved to White Cottage in Bridegate Lane (demolished many years ago). They had one child, a daughter, Ivy Kathleen born in 1908 and baptised in the church. Albert volunteered for service during the war but was rejected because he suffered from asthma. In 1924 he was working in Ab Kettleby and fell from a loft, severely injuring his hand and back of his head, many stitches being required, but he recovered from this accident. In 1929 the family moved to Ab Kettleby, by which time he had been a member of the church choir for 22 years. Albert died in 1949.

In 1913 Lily also married in the church, the groom being tailor Alfred Pepper, whose parents were from Melton Mowbray. Albert was living in Moreton in Marsh and, after a honeymoon in Skegness, the couple went to live there, but they later moved to Melton. Lily worked with Albert as a tailoress. They had one child, a son, Rowley. The three of them spent each Christmas at Rose Cottage. In 1925, aged 38, Lily died. She had been unwell for over a year, having been seriously ill with pneumonia. X-rays showed “internal trouble”. She returned home but gradually declined.

Donnie was another member of the family who was very prominent in village events. He was the energetic secretary of the cricket club from 1913 until 1927 and after the war was secretary of the Vale of Belvoir Branch of the British Legion, which job included organising a variety of fund-raising events aimed at building premises for the Legion in Hickling. In 1919 he organised two cricket matches between Demobilised Soldiers and AF Shelton’s eleven, he being part of the doubly-victorious soldiers’ team. Like Albert, he played billiards for the village Institute team. In June 1917 he became the fiftieth person from Hickling to join the forces, being part of the Notts and Derby Regiment. A talented musician, he joined as a bugler. He returned home on short leave in the October. Following the great offensive of 21 March 1918 news of him ceased. In May, however, Sarah Ann received a letter from him telling her that he had been taken prisoner on the Somme on the day that he went missing and he was now on his way to a prisoner of war camp in Germany. He assured her that he was quite well. She later received formal notification of his capture, which also told her that he was with Vincent Walker from Hickling and Ted Huckerby from Long Clawson. They were employed on a farm and generally treated fairly well. Although their diet was mainly vegetables, this was supplemented by parcels from the Nottingham Red Cross Comforts Fund. He and Vincent returned home in December after nine months as prisoners and were said to look “well and hearty”. Bells rang in the village to welcome them and flags were displayed. His niece Maggie remembered the day: “The church bells rang, people stood outside Rose Cottage waiting for their arrival from Widmerpool Station and there was such a cheer when the horse and cart drew up and the ex-prisoners were home again”. For many years Donnie played the Last Post and Reveille at the annual remembrance service. He married Evelyn Mary Sims in Ashbourne in 1932 when he was 42 and she was 26. They had four children, George Alvin, Daphne Ellen Ann, Charles Donald and Christine M, all of whom were baptised in the church. He had taken over the butcher’s business and when Sarah Ann died in 1930 he bought Rose Cottage. In the 1939 register he was described as a master butcher. Donnie died in 1966.

Rowley, too, was a talented musician and performed in concerts in the village and he and Donnie accompanied the early Christmas morning carol singers on the cornet and violin. He also sang in local concerts and, like Donnie later, he was secretary of the cricket club. In October 1912 Rowley emigrated to New Zealand. At a farewell tea in the chapel school room reference was made to his geniality and his readiness to assist in any musical services in the chapel. He received many gifts, including from the rector, and spent his last evening in Hickling with his family. In 1916 he married Miss Barbara Bellini. He joined the army in New Zealand but was discharged in 1917 as medically unfit. He was the only one of the siblings still to be alive in 1976 when his niece Maggie Wadkin (nee Simpson) wrote her memories of her childhood.

Emmie also performed in village concerts. In 1901 she was a guest in the house of Elizabeth Buxton in Kinoulton. Mrs Buxton’s daughter Mary, who was also in the house, was a pupil teacher at the Hickling school. In 1911 she was in the household of grazier William Henry and Mary Edgson in Hickling, working as their domestic servant. Emmie married a local grazier’s son, Thomas Albert Rose, in 1917. He was then a gunner with the RFA. Their honeymoon was just a couple of days in Nottingham before Thomas returned abroad. They had a son, Alwyn Cecil, in 1920, at which time Thomas was a sawyer. Their daughter, June Mary, was born in 1932 when Thomas was a farm labourer and they were living at Rose Cottage. By 1939 Thomas was described as a dairy farmer. Emmie died in 1948 aged 55.

One can only speculate as to whether Charlie and Cecil would have returned to Hickling after the war to take part in the running of the family business or whether they would have established their own businesses elsewhere.