We have a small number of headstones which have all the characteristics of a Belvoir Angel headstone but without any angels. We don’t have any real explanation for this but they are all smaller and lower than those with Angel carvings and they are often clustered amongst the Belvoir Angel headstones:

- The Belvoir Angels represent a distinctive type of naive art which emerged out of the traditions of the 1600s. The headstones without Angels may simply be the fore-runners of the Belvoir Angels with some crossing over in time.

- They may be a style-choice or perhaps lettering without imagery was cheaper?

- They may just be the work of a different stonemason.

- It is understood that Belvoir Angel headstones were often damaged and even removed by puritanical folk who disapproved of the imagery and symbolism; perhaps the Angel headers were removed from some of these stones? Some do show slightly rough edges on the tops and even parts of patterning slightly cut off. The grave of Mary Robinson is an odd shape which may indicate angels have been removed from the top corners. However, because of the rough hewn characteristic of the Belvoir Angel stones, it is impossible to be sure.

- Perhaps there is one further explanation which is highly speculative. The Angels are very much a trademark and easily identifiable; could the masons have removed some of the Angel carvings themselves? Perhaps falling out over design or payment or any other reasons that local people fall out with each other?

Examples:

The following examples are all slate headstones from the period that the Belvoir Angel stonemason/s were active. Some share clear characteristics with the Belvoir Angels (the style of carving and two double-sided stones) but others are included here to give a sense of other work of the period and, also, possible transition stones towards the end of this period.

The first five, below, seem to be the most likely possible examples of damaged headstones; however there are surviving examples in the churchyard with Angels and from similar dates which implies that damage didn’t occur as a concerted effort to wipe out these stones in a given period of time.

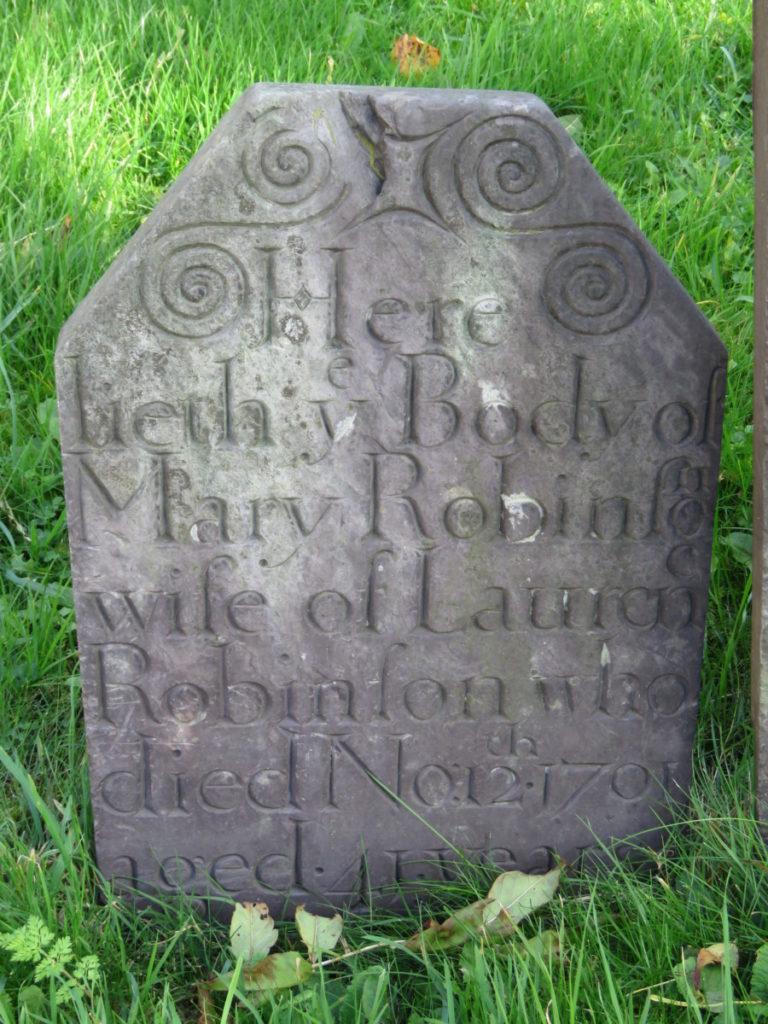

Mary Robinson 1701 & Laurence Robinson 1725: double-sided

This headstone is a very unusual shape and does have the appearance of having the top and the top two corners removed. If this is the case then it would have been an unusual stone for Hickling in its original form – the only other example that we have for the Angels occurring in the top corners (instead of across the top) is much later, in the 1750s.

Nevertheless, there are signs that some of the patterning has been cut through and even that the sides may have been cut down, too. The lettering and the double-sided form are characteristic of a Belvoir Angel stone but it may simply be a slightly quirky early example. It does seem likely to have been crafted by the same stonemason as the Belvoir Angel headstones.

The later carving on the reverse for Mary’s husband Laurence does seem to add some clues: this carving is much later and has a truncated border. The lettering is also of a later style and is unlike the Belvoir Angel stonemason’s work – perhaps he/they objected to going back to such a vandalised stone?

Mary Collishaw 1704 & John Collishaw 1728: double-sided

This stone is very low level but shows the characteristic horizontal lines which usually divide the stone into three parts; the Angel motif, details of the individual and an epitaph at the bottom. This stone only appears to have its middle section.

It is also one of the rare double-sided grave stones with the added oddity of a date carved onto the top edge of the stone: February 6th 1704 (which tallies with Mary’s burial records in the Parish Registers which give her date of death as 7th February 1704).

The carving on the reverse for her husband John’s death in 1728 is similar in style and seems to be the work of the same stonemason. Unusually, the epitaph is at the top and it is possible that this was carved at the time of Mary’s death and a space left for John’s name when the time came. It also has the characteristic horizontal dividing lines.

Hugh Gill 1708

Hugh Gill’s stone is the third of these headstones which have a very strong resemblance to the Belvoir Angel headstones. The lettering and the layout are both strongly reminiscent of the Belvoir Angel headstones and the patterning at the top of the stone may indicate that a section has been removed.

Richard Faulkes 1718

Richard Faulkes’ headstone is a small fragment but it has all the characteristics of the middle section of a Belvoir Angel headstone and the lettering is intruding on the top edge of the stone which seems unlikely to have been deliberate. Richard’s mother, Dosie (Theodosia) Faulkes is mentioned on this stone and her death in 1727 is marked with a full Belvoir Angel headstone.

Eliz. Hardey 1721

Although the top edge is badly chipped, this headstone also has all the characteristics of the middle and bottom sections of a Belvoir Angel headstone; the lettering and style are consistent and the patterning and lettering at the top of the headstone intrude unnaturally on to the top edge.

John Cornforth 1729

John Cornforth’s headstone has some similarities with later Belvoir Angel headstones in the Churchyard; the lettering and patterning is more flowing. Although it is made from Swithland slate it lacks the 3 section form and lacks the characteristic lettering style that we would expect. It may be from the same family of stonemasons but it seems unlikely that it has lost its Angel header. The only cause for hesitation would be its remarkable similarity to its neighbour – the headstone for Ann Faulks – which has very similar lettering but also has more of the characteristic Belvoir Angel features.

Ann Faulks 1745

This stone has a fully squared off border which makes it unlikely that it has lost its header. However, it shares a number of characteristics with the traditional Belvoir Angel; it is sectioned in the same way, for example. Like John Cornforth’s stone (above) the lettering is more flowing and better organised than would be expected; it is possible that these two stones are the work of a different member of the family business and illustrate steps in the progression away from the traditional stones.

Thomas Greasley 1746

As above, this headstone has a more flowing and better organised aspect with the individual’s details part of the flowing patterning instead of the separate Angels header; it also has a fully squared border which implies that it is a complete stone. Many of the Belvoir Angel characteristics are present, though – including the epitaph below a horizontal line at the base. It is next to the full Belvoir Angel headstone of Mary Wilkinson dated 1849 and they do appear remarkably similar and may have emerged from the same workshop.

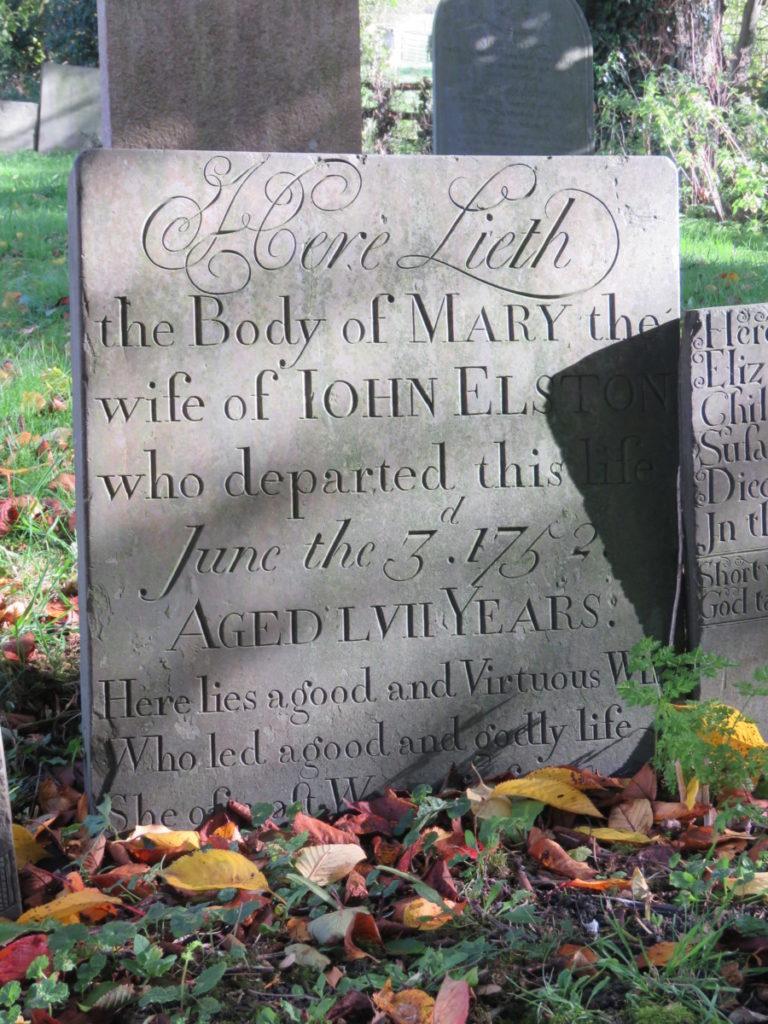

Mary Elston 1752

It is likely that this stone is complete as with the previous examples. It is well spaced and planned and only has general likeness to the Belvoir Angel headstones; the three sections, for example, although there are no horizontal lines. Indeed the lack of any border and the closeness of the engraving to the top edge are notable. This is a Swithland slate headstone and may simply be contemporary to the Belvoir Angels or the work of a later hand in the same workshop.

Mary Rasdal 1762

Mary Rasdal’s headstone is very damaged and worn but it does seem to show signs of having been cut down or even left unfinished. It has rudimentary squares in the top two corners and, unusually, has a large empty space below the epitaph. It does have the horizontal dividing lines characteristic of a Belvoir Angel headstone.

Note: the latest surviving Belvoir Angel headstone in Hickling is dated 1758 (Joseph Daft).

Thomas Skillington 1764

It is possible that this could be an example of a transition piece; it has the horizontal dividing lines and writing style of the Belvoir Angel headstones but the header is deliberately formed around the opening of the individual’s details and the urns that form the patterning are more typical of the more formulaic pattern book designs emerging from the mid-1700s.

Joseph Bampton 1768

1768 is late for the Belvoir Angel tradition and this headstone is identical in style, shape and design to that of Mary Rasdal (above). The squares in the top corners seem more deliberate in this example but it also has the rudimentary style of the traditional Belvoir Angel headstones. Also made of Swithland slate this may be a later, simpler headstone from the same workshop as the Belvoir Angels.